A Man Called Ove (En man som heter Ove) is a humanist piece of new Sweden cinema originally released in 2015, reminiscent of last year’s excellent work, Rams, from nearby Iceland. Both films carefully explore emotion after tragedy and offer knockout protagonist and supporting character performances. While the storyline here is not new—a group of young souls soften the heart of a persnickety elder—the film’s elegance, led by writer/director Hannes Holm adapting the story from Fredrik Backman, is pitch perfect in situating us as bystanders with just enough distance from the characters to develop a healthy pathos. By healthy pathos, I mean that we

Of course, not everyone mourning the death of a loved one must be a jerk (Ove’s de rigueur attitude is yelling and calling everyone an idiot). From florists to neighbors, even giving up on old friendships, Ove has taken a vow, it seems, to demonize others. Classic bully behavior makes the bully feel superior by making others feel badly, but in Ove’s case, he never seems to get satisfaction from being crotchety. Nor does he experience a reprieve. The closest he gets to calmness, and a sentimentality coated in softness and not exasperation, comes through his daily visits to the grave of his deceased wife, Sonja (Ida Engvoll). One afternoon, he makes a bed of newspapers by her tombstone, extending his hand over her plot, as if they were about to fall asleep together. This single gesture packs more Pablo Neruda into the film than any other. Effective for showing the depth of his love story, it also makes clear the complexity in suffering, and its impetus and abilities to be concise in mourning, acceptance and moving on. New York City visual artist James de la Vega reminds us, “Be mindful even when your mind is full.”

It is thanks to Parvaneh (Bahar Pars in an extraordinary performance—more of her anywhere, please) this shift happens. A very pregnant Parvaneh, her husband and two children are Ove’s new neighbors. Once manager over their housing village then ousted by his good friend, Ove has declared himself the de facto chief and checks the property daily showing no mercy to anyone deterring from policy. Parvaneh is as open-hearted and full of endearment for others as Ove can be obstinate and unfeeling. They share a lively sense of humor; while Ove is driven by angst (his ultra-moralism, almost a parody of itself, is often hilarious to watch), Parvaneh’s glee is a go-with-the-flow merriment that lifts others around her easily. A sharp empathizer with a strong maternalistic spirit, she takes an interest in Ove to help him overcome his stuckness. The two form an extraordinary friendship, a next of kin relationship, presented with language and closeness that effortlessly weaves through ease, joy and conflict, that the two could barely be more real.

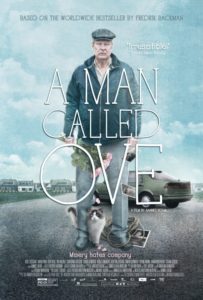

Rolf Lassgård in “A Man Called Ove.”

As much as A Man Called Ove, then, is about love—love for spouse, love for first family—it is equally about the transformative power of friendship, or more generally, of caring for another. Holm integrates this message by flashing to Ove’s childhood and his story with Sonja, replaying his relationship and the tragedies suffered with his parents to the moments of magic and heartbreak with Sonja. Parvaneh, along with their young, hip, couch potato and funny neighbors, are a resounding force of presence. Her pregnancy juxtaposes Sonja’s passing and lends the most obvious light to the decision Ove must make to move forward or live in the past. As he tells Parvaneh early on, there was nothing that existed before Sonja, and there will be nothing after her. She looks at him and simply says: “I am something.” What Ove learns is not that letting go is easy, nor that it can become easier over time, but that placing your attention on others—their struggles and their joys, and welcoming and joining their living—can bring the happiness of community and a generosity of shared experience. Although not the comforts of the love of your life, this is a love that can fill to the edges.

Dina Paulson-McEwen

Latest posts by Dina Paulson-McEwen (see all)

- Interview with Hannes Holm, writer/director of A Man Called Ove - April 15, 2017

- Unknown Pleasures and Paul Thomas Anderson’s Junun in Berlin - July 3, 2016

- 10 Best Things About the 2016 Oscars - March 1, 2016