Yalini (Kalieaswari Srinivasan), a Sri Lankan refugee working as a housekeeper in France, explains to Brahim (Vincent Rottiers), the drug kingpin of their neighborhood, that in her culture a smile indicates understanding, expressing pain and happiness equally. The French, she says, think she is making fun of others or confused. The ability to communicate well with people close to you and the outside world is a central privilege identified in Dheepan, a capacity eluding its protagonists. The film is set during the Sri Lankan civil war (1983-2009), and the characters we come to know as Dheepan (Jesuthasan Antonythasan), Yalini, and the young Illayaal (Claudine Vinasithamby) were killed during the war. Our protagonists are assigned these identities and as a family unit, they

But this story belongs to Dheepan, a gentle spirit given a name that means illumination, who is assigned the job of caretaker at an apartment complex outside of Paris. He is also the caretaker of his new home, a role he fully commits to, desiring a new, loving family life to replace the devastation of his first family killed in the war and the brutality he lived as a Tamil Tiger. When the drug business turns violent, Dheepan reluctantly but smartly assembles a defensive unit to protect Yalini and Illayaal. Dheepan’s central conflict is resolving not only his memories of war, but the rebel patriotism they stir up, a wound reopened when he is visited by his former Colonel and asked to raise money for the Tigers. When Dheepan says the war is over for him, he is viciously beaten by his former chief.

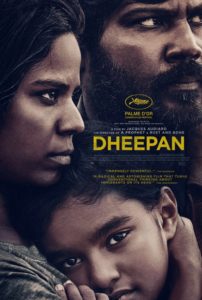

Dheepan, also the winner of this year’s Palme d’or at the Cannes Film Festival, excels as a true-to-life filmic portrait imagining one family’s refugee experience. In a beautiful scene, the camera following Dheepan as one would a sartorial master, he makes an elegant, nifty toolbox using scraps and anything he can find around the house. The director (Jacques Audiard) is provocative, questioning how we judge others and specifically, refugees and people recovering from various PTSDs; to look beyond a neat synopsis of what they might have endured and see that hardship and trauma can result in a special type of grit and brilliance. The UN reports that over 2,500 refugees and migrants have died attempting to cross the Mediterranean to Europe so far this year, while contention in the U.S. and Europe over setting immigration and refugee policies persists, making the film extraordinarily relevant, if not depressing. Nicolas Jaar created its electrified, understated score, his first music credit on a feature-length film, though he is perhaps better known for club music. A quick listen of his tracks gives the same feel of global beats, overlaying shrill, anticipatory, and dreadful chords that punctuate the film’s most tense and sensitive moments.

The film continues a shadowy mise en scène, suffusing its characters in darkness or showing them at a distance, with long shots of Brahim’s drug army resembling worker ants in puffy coats as they move their bodies quickly, pushing their drug business. Three flashes to dreamlike images – two of a majestic elephant moving slowly through, we suppose, the rainforests of Sri Lanka, also likely symbolizing the head of Hindu god Ganesh, and one of a man’s hand breaking ceiling halogen lamps – add a Charlie Kaufman shot to Dheepan, punctuating its message of endurance where staying present requires a life or death precision.

Dina Paulson-McEwen

Latest posts by Dina Paulson-McEwen (see all)

- Interview with Hannes Holm, writer/director of A Man Called Ove - April 15, 2017

- Unknown Pleasures and Paul Thomas Anderson’s Junun in Berlin - July 3, 2016

- 10 Best Things About the 2016 Oscars - March 1, 2016