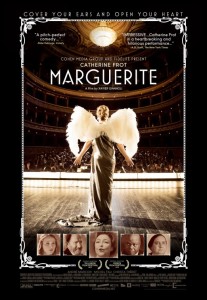

“Music is the stuff of dreams,” declares a psychic medium in the heart-struck 2015 French film, Marguerite. Parisian opera singer Marguerite (Catherine Frot) lives in a dream world as a venerated soprano, and we are acutely aware of our participation as voyeurs; our vision, by contrast, is startlingly awake, or in other words, realist. I nearly longed to feel the inside of her madly constructed and confident world, where music wallpapers every encounter and sits at the heart of each relationship. Yet, it was exhilarating to be carried as a bystander, which, of course, is the deliverance of the film’s director, Xavier Giannoli. His prior films have dealt with elements

Giannoli injects a punchy nuance to the fourth wall with Marguerite. The film’s characters and audience (us) are united, because we know she cannot sing. Marguerite believes she can and so inverts the experience of the fourth wall. She is the background and foreground, the protagonist and silent antagonist, the center stage and its frantic, backstage action. Her consciousness not only moves along the story, it is the story. In this way, Marguerite becomes even more of an anomaly, one of the most astonishingly real and self-deceptive heroines of recent cinema, a fantasy figure whose existence is attracting partnerships and creating stories to preserve her worldview. Yet, Marguerite’s world is ultimately exclusively hers; her vision belongs only to herself.

Her husband, Georges (André Marcon), exists somewhere between mortification and loyalty. He fears telling Marguerite the truth, while suffers her assuredness that she is a masterful artist. His position comes with its own irony, evident when he accuses friends of complicity by being dishonest about her voice. When Marguerite says an audience brings music to life, and she wants to sing in a theater, Georges tells her that music performed in private settings has greater value. Marguerite wants a stage, a kind of reciprocity, and Georges, obviously, does not want her to sing publicly. Underlying their exchange are more persistent ideas about longing, possibilities for resilience, and the completeness of experience.

Marguerite is a love story, above all. She never wants to sing unless her husband is there, yet Georges habitually arrives late. Marguerite wants to make him proud, the more profound delusion of the film. And Georges wants his wife back, not the “freak” she has become, but her reality eclipses that possibility. When he accepts who she is, he becomes a passionate caretaker, Marguerite’s main cheerleader and protector. “There is nothing more beautiful than applause, except for the gaze of the man you love,” says a voiceover. Beyond artist friends and stage opportunity, Marguerite needs the love of her husband. When Georges shows up and catches her, it is her most accomplishing act.

Dina Paulson-McEwen

Latest posts by Dina Paulson-McEwen (see all)

- Interview with Hannes Holm, writer/director of A Man Called Ove - April 15, 2017

- Unknown Pleasures and Paul Thomas Anderson’s Junun in Berlin - July 3, 2016

- 10 Best Things About the 2016 Oscars - March 1, 2016