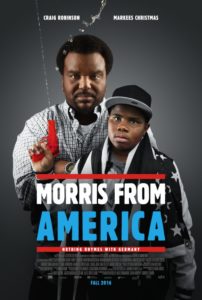

Morris from America is about xenophobia and stereotypes, bullying, living as expatriates and mourning the death of a wife and mother, but mostly it is about the tenacity carried out with a striking tenderness by Curtis (Craig Robinson), a newly single dad taking care of his teenage boy, Morris (Markees Christmas) in Heidelberg, Germany, where they are, as he puts it to his son, “the only two brothers” here. For Morris this looks like, at his school and youth center, being treated with a partly fetishized fascination by one of his classmates, Katrin (Lina Keller) and with racial slurs by another, and being accused by the teacher of

Morris is not a character to sympathize with, and I mean that with the highest respect: He wouldn’t want you to feel bad for him, so the whole feeling-bad-for Morris thing would backfire. He is an incredibly sharp, self-aware and self-confident thirteen-year-old with a talent for freestyle rapping who could be a poster child for “sticks and stones may break my bones but words will never hurt me.” Not that this is necessarily a good trait; the cruelest bullying comes from a boy who says Morris would do them all a favor by killing himself, striking at a deeper message the film introduces but does not explore. The expatriate life is challenging with its complexities of otherness, but director Chad Hartigan seems to suggest that bullying can target anyone perceived as different. Even if someone has a strong sense of self, they may not also have a positive reinforcement caretaker at home, as Morris does in Curtis, or a sisterly figure watching out for him/her, as Morris does in Inka (Carla Juri), his German tutor. The racism exposed in the film lives overtly in questions Morris gets from classmates such as isn’t he good at basketball and can’t black people dance well to a more nuanced chilling scene where Morris raises a plastic gun filled with water Katrin has given him in a prank, looks in the mirror at himself and shoots it. This scene cannot be seen without bringing to mind twelve-year-old Tamir Rice who was playing with a toy gun and shot by the police in 2014. Morris’s German, white classmates are able to exist in a way that Morris, as a black boy, cannot.

A gorgeous sequence happens when Morris visits a castle in Heidelberg, and the statutes and people around him begin moving along with his rap music, which plays through his earbuds most of the time. The film is provocative also about checking assumption and privilege when it comes to art, looking at what is considered fine or “cultured” art, such as museums or playing the flute, and their relationship to the lived art that is surviving through finding joy, friendship and music in the everyday, and contrasted finally to the musical arts Morris survives by and are what he lives for – what he lives to become more of. The friendship, and perhaps for Morris the first real crush, he and Katrin develop is significant because they end up helping each other see more clearly the world around them and the potentials each of them have to follow their dreams as the free, exploring spirits they are. Youth is not just an age, Morris’s teacher tells them early on, it is a state of being. When Morris and Katrin are out dancing one night, Inka happens to also be there. She tells him to take his time being young, that being old will come. “Nobody dances like you, Morris,” she says.

Dina Paulson-McEwen

Latest posts by Dina Paulson-McEwen (see all)

- Interview with Hannes Holm, writer/director of A Man Called Ove - April 15, 2017

- Unknown Pleasures and Paul Thomas Anderson’s Junun in Berlin - July 3, 2016

- 10 Best Things About the 2016 Oscars - March 1, 2016