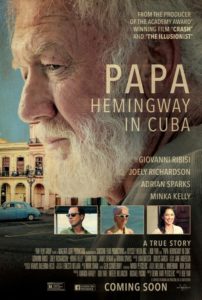

At the beginning of Papa: Hemingway in Cuba, Ed Meyers (a lackluster Giovanni Ribisi), a thirty-something journalist with the Miami Globe in 1959, claims that Ernest “Papa” Hemingway (Adrian Sparks), saved his life. He says the author helped him become a writer and provided him with hope during an orphaned childhood. After Ed was fired for misspelling “maybe,” he stayed up nights during his probationary period copying each of Ernest’s short stories. “I learned grammar, dialogue,” essentially everything, he tells him and his wife, Mary (Joely Richardson), on

Ed says, “I needed to tell him how much he meant to me.” The need to tell, to express something inside out however crazy or messy, is a good way to describe what motivates the true-story characters in Papa: Hemingway in Cuba, and also, unfortunately, the director’s (Bob Yari) dizzying scene cuts, soap opera mise-en-scène, and glaring metaphors (a cat pounces and catches a mouse in front of Papa’s house). I was most moved by the post-script of the film, where Ed’s character is revealed as journalist Denne Bart Petitclerc, who wrote the film’s screenplay. Mr. Petitclerc remained close with Mary, and the post-script says that Ernest killed himself eighteen months after the film’s story ends. In the climax of Papa: Hemingway in Cuba, Ernest attempts suicide in front of Mary, Ed, and their poet friend, Evan Shipman (an excellent Shaun Toub), only throwing down the gun when Mary says she cannot live without him. The next moment that follows, the final scene, is Ernest typing in his study after a prolonged stretch of writer’s block.

Most of Papa: Hemingway in Cuba is concerned with trying to care about Ed’s childhood into adult struggle (because, how fine and talented is Debbie, and can he please pull it together?). He wonders blankly in a voice-over about everyone’s Achilles heel: “Even though I loved her, how could I give her something I had never known?” The problem is Ed rarely shows emotion, except for his thankful stammering when Debbie is seducing him. Abandonment is done so well in Cider House Rules and Sherrybaby, but when Ed’s father leaves him, the scene is a cliché. It is hard to see Ernest as Ed’s mentor and father when there are no signs of him appreciating Ernest’s generosity and gentle coaching. “The only value we have as a human being are the risks we are willing to take,” he tells Ed, wisdom he absorbs to become a less broken man. Or, at least this is what we are meant to believe; because he eventually tells Debbie he loves her.

Elongated scenes showing the painful marriage between Ernest and Mary give our most graspable peek at inner lives in Papa: Hemingway in Cuba, due largely to Joely Richardson’s astonishingly vulnerable, acerbic performance as Mary, the fourth love of her husband. The anguish of Cuba and mounting revolution between the U.S. backed Batista government and Fidel Castro and his rebels gaining power is a backdrop (not a background), and any attempt to make Ernest seem like he was “for the people” falls flat. (A poorly enacted side plot uncovers the FBI and Batista working together to kick Ernest out of Cuba, the exact reason unclear.) Papa: Hemingway in Cuba fails as a complete film story by neither braiding together or dissecting individually these sufferings. Does it explain how Hemingway’s heartbreak fueled his brilliant writing? Is it about overcoming emotional trauma and learning to love? Is this a story about extraordinary women becoming instruments to men considered more extraordinary? The aspirations go on.

Reaching for the Moon, a 2013 film about the relationship between American poet Elizabeth Bishop and Brazilian architect Carlota de Macedo Soares set in Brazil from the 1950s-1970s, is a more successful ethno-romantic project about artists and catastrophe in Latin America. The film focuses on the intimacy of its characters and political situation of the country through tight dialogue and fully uses the range of its actors. If we look only at Ed, the pathos is hard to find. Ernest’s struggle of abandoning his true love and their child and the remarkable work he produced offers love, family, and passion pathos, but, the story of a country revolutionizing? Yari gives us only a snippet of this. As Havana becomes the new American tourist destination and lists on preparing your 2016/2017 Cuba trip circulate, not to mention Hollywood has already jumped on projects in the country, this film had an opportunity to feel a lot more relevant. Papa: Hemingway in Cuba deserves kudos for being filmed on location, including at the Hemingway house in Havana, now a public museum. I would like to say I got lost along the way, but the film never had my full attention.

Dina Paulson-McEwen

Latest posts by Dina Paulson-McEwen (see all)

- Interview with Hannes Holm, writer/director of A Man Called Ove - April 15, 2017

- Unknown Pleasures and Paul Thomas Anderson’s Junun in Berlin - July 3, 2016

- 10 Best Things About the 2016 Oscars - March 1, 2016