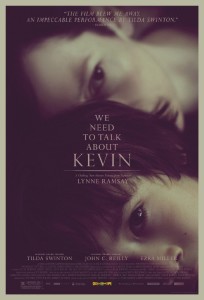

Effortlessly editing back and forth in a winding timeline, the film gives us glimpses of the complex psychological combat between mother and son right from the outset in which Kevin’s birth is portrayed as a wailing argument between two bodies that blossoms into outright contempt as the boy hardens into adolescence. Androgynous young Ezra Miller (TV’s Californication) sharply perfects the demanding role of Kevin in his boiling-over teenage years and proves an ideal sparring partner for Tilda Swinton as his cold, bohemian mother Eva. After her career as a free spirit travel writer is interrupted by Kevin’s arrival, Eva shows early signs of indifference to the boy in some great scenes with the young sinister kid (Jasper Newell as the scowling tot). Knowing what Kevin will eventually unleash hangs over these fruitless attempts at bonding (Kevin refuses to roll back a ball; he stays mute until late in life). Unafraid to be seen as unlikeable, Swinton is tasked with showing frustrated disdain instead of motherly concern. In the Lifetime movie someone a lot less sinewy and brittle as Swinton would likely take on the role, but would not do it the same thoughtful, stoic justice.

Rounding out the crack cast, John C. Reilly plumbs his Everyman persona in the fuzzy role of the doting, enabling father of a boy he refuses to see through. Kevin is a bastard to his little sister, animals, and especially his mother but dad just encourages him to keep honing his fateful marksman skills with arrows in the sprawling suburban backyard. Ramsay’s role as a European outsider serves her well in dissecting the thick nuclear family façade to see the unease within; an emotional state of chaos is inferred through the numerous Jackson Pollack-style splashes of color and oversaturation of light (Kevin’s pillow resembles a Pollack, the little boy throws paint all over his mother’s work, scenes are bathed in red, etc.). A full enjoyment of Ramsay’s mastery is not possible without making these pointed connections.

Unlike the Nancy Grace’s of the world, Lynne Ramsay does not wag her tongue at societal dysfunction and tragedy; she avoids kneejerk diagnoses by abruptly cutting scenes and beginning new ones in the aftermath of things and working back from violence into a clear-eyed investigation. Much of the film takes place in the present moment as Eva plays the martyr by remaining in the same town as a whipping post for the community’s grief. Swinton is a hollow-eyed shell with little dialogue as she is confronted by people still bearing her son’s injuries.

Don’t let the weighty subject matter keep you away from a film that never becomes as exploitative and offensive as elements of Gus Van Sant’s over praised Elephant (which used Columbine as its reference). We Need to Talk About Kevin has the luxury of being fiction and thus is easier to watch as a biting, brilliantly acted piece of dramatic entertainment made by an artist with an exciting visual and sonic pallet fashioning cinematic order out of our grim social chaos.

Gregory Fichter

Latest posts by Gregory Fichter (see all)

- Bela Lugosi’s Not Really Dead: A Vampire Movie Primer - November 18, 2011

- Ten Great Summer Grindhouse Movies - August 16, 2011

- The Ten Best Johnny Depp Movies - May 19, 2011