The end of the “classic period” is considered to be Orson Welles’ 1958 Touch of Evil, and Sam Fuller’s The Naked Kiss released in 1964 is considered by most to be the last film noir. There were a few attempts at noir in the 1960s and 1970s, but the genre’s real resurgence didn’t start until the 1980s.

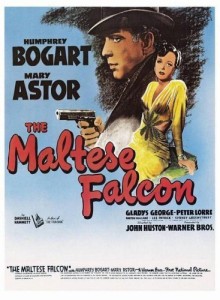

The term “film noir” was coined in 1946 by French film critic Nino Frank and was further defined in 1955 by French writers Raymond Borde and Etienne Chaumeton in their book A Panorama of American Film Noir. While the films of the classic period were not produced consciously as noir, at least up until 1955, they all had thematic and visual similarities which identify what eventually became known as noir. The stories were influenced by the hard-boiled detective novels of Chandler, Hammett, Cain, and others and the striking visuals were heavily influenced by cinematographers and directors who came to the States from Germany before and during World War II. Most of the films were made inexpensively on studio sets and back lots, many as “B” movies. The location shooting done in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and New York have made them the quintessential noir cities.

No remakes make the list of neo-noirs found below. Four period films do. I tried to include only those that had a classic noir structure with a protagonist, a femme fatale influenced by her bad guy husband/boyfriend, and a narrative and feel about it that could definitely be considered noir. All were produced in the US after 1964.

There are well over a hundred neo-noirs to choose from. Films not making this list, but also very good and worth watching are: The Black Dahlia, Basic Instinct, Blue Velvet, Bound, Dark City, Femme Fatale, Lost Highway, The Hot Spot, Klute, Miller’s Crossing, Sin City, and Taxi Driver.

____________________________________________________________

15. After Dark, My Sweet

There is a lot of the Terry Malloy “I could’ve been a contender, I could’ve been somebody” in Collie, but Collie lacks Terry’s moral compass. He thinks he’s smarter than he is and his obsession with Fay makes him even less so. The remorse he feels only makes his fate more certain. It all ends about as badly as it could.

14. The Grifters

Each has his or her own desperation and sees the other as a way to make the big score, but none of them are capable of trust or forming partnerships. Myra and Lily both want a piece of Roy who wants nothing to do with either of them. A three-way power play ensues that gets grimmer with every turn, climaxing in a violent ending that is very noir.

13. The Two Jakes

While many post WWII noir protagonists are haunted by the war, Jake is haunted by a different past: the part he played in the death of Evelyn Mulwray and his inability to save Evelyn’s daughter, Katherine. And while there is some redemption in this story it is of little value to him. In the last scene, Jake pretty much sums up the critical sentiment of the noir protagonist: “The past never goes away.”

12. The Long Goodbye

This film is quirky – he lights a cigarette in every scene, keeps a cat in his apartment and has very interesting neighbors – with some bizarre dialogue and a nicely complicated plot. Marlowe looks for the truth when his friend is accused of killing his wife and when a woman’s husband disappears. If it wasn’t obvious up until now, the ending very quickly makes the point that this version of one of the great classic noir detectives is very different than the 1940s version.

11. Devil in a Blue Dress

Easy Rawlins is the classic noir protagonist: a good, but morally ambivalent man who abandons his better judgment for something he knows is wrong. This film has a great 1940s mood along with bad cops, crooked politicians, a femme fatale and a psychopathic killer you can’t help but like. It also has something that classic noir rarely touched on: racism in post-WWII America.

10. Memento

Leonard’s loss of control and inability to discover the truth is all part of the life of the noir protagonist. What makes this film great is in the way the narrative unfolds: the story is told backwards with time loops that create a confusion for the viewer that parallels Leonard’s. Leonard is doomed to living for vengeance that is unobtainable; even if he succeeded he wouldn’t remember it. But he will always have his last memory and with it his strongest emotion: the grief over the loss of his wife.

9. Mulholland Drive

Diane’s confused, schizophrenic life plays out in an extraordinary story that has mystery, suspense, and bizarre, unexplained plot points. Diane has created in her mind her own Hollywood movie and her own noir existence of alienation, loss, guilt, and revenge.

8. Blood Simple

It’s hard to say which of the two guys is getting screwed the most. The non-classic femme fatale is just a little bit smarter than the rest of the characters who really aren’t very smart. As the story unfolds each character in turn goes from being the most sympathetic character to the least likable. There are a lot of twists and turns in this one which may be what the memorable last shot is all about – literally.

7. Red Rock West

Suzanne is one of the great neo-femmes and even looks like a skinny Ava Gardner. The wheels are spinning in her head all the time and she has her accomplice in the completely morally compromised Michael whose wheels are spinning in something other than his brain. He seems like a nice enough guy, but is willing to play by Suzanne’s rules. Red Rock West got instant noir credibility by being a “B” movie that went direct to video before becoming an art house favorite.

6. The Last Seduction

Mike is way out of his league and Bridget maneuvers him into the plot by telling him he has to prove his commitment to her by doing this one little thing for her. The poor guy sees how bad she is but it doesn’t matter, he’ll do anything for her and is willing to overlook her faults. She puts her cigarette out in the pie that grandma had baked for him, but he no longer cares.

5. Point Blank

Time and space are a little out of sync as the film features flashbacks and jumps that confuse reality as well as Walker’s state of existence. We don’t know if Walker is living the events or dreaming them – both of his past life and his quest for revenge. He’s the lone wolf, a man that wants no allies; his separation from all that is around him creates an alienation that is complete and, for Walker, without ending.

4. Body Heat

The story owes a lot to Double Indemnity: a woman with an unwanted husband and an obsessed, easily manipulated lover – this time a not so smart lawyer. Matty Walker hooks and lands Ned Racine in one night and draws him into her very well thought out plan. She manipulates Ned into murdering her husband so they can be together, all while making him think the whole thing is his idea – and that she really loves him. By the time he figures it out it’s too late. For the neo-noir femme survival, doesn’t always mean winning. In noir, sometimes the winners don’t even win.

3. Blade Runner

Det. Rick Deckard’s assignment is to “retire” four outlaw cybernetic androids that have come back to earth and are considered dangerous. Deckard starts his investigation at the bad guy Tyrell Corporation, maker of the “replicants.” There he meets the beautiful Rachel who is a different kind of femme fatale. She’s not bad but there is something bad about her: she isn’t human. She is Tyrell’s latest model, programmed with memories that make her think she’s human.

Deckard’s obsession with Rachel is immediate – she’s both beautiful and forbidden. He now has to complete his mission and somehow save Rachel. As the two are drawn to each other their fates become intertwined and Deckard realizes the ultimate existential angst: what does it mean to be human?

2. L.A. Confidential

The plot couldn’t be much more complicated and the noir detective is a composition of three cops: one tough guy, one good guy (sort of), and one narcissist who is only in it for himself. Two of the guys become involved with the same call girl; one wants to use her, the other just wants her. And all of them are part of the corruption in the police department and complicit in murder. Very much a three act play and in the third act the good guys are finally separated from the bad guys. This is one of the best films of the 1990s.

1. Chinatown

When Cross tell Gittes, “You may think you know what you’re dealing with, but believe me, you don’t,” he pretty much defines what it means to be a noir detective. He also foretells future events that Gittes will never completely understand. Gittes is all around the edges of the truth and by the time he sees it, he is too late. The story ends in one of Hollywood’s bleakest and best scenes. It’s the only one that takes place in Chinatown.

Gregory Small

Latest posts by Gregory Small (see all)

- The Best B-Movies of the 21st Century - May 26, 2015

- From Vampires to Cave Girls: The History of Hammer Films - October 14, 2014

- Space Travel, Alien Invasions, and Atomic Monsters: The Best 1950s Science Fiction Films - June 11, 2014