We have always been stargazers. We look into the night sky and wonder what is out there and if future generations will travel to far away worlds. And we wonder what kind of world we will see in our lifetime and what kind of world our children and their children will inhabit. We have romanticized about and expressed our hopes for the future in literature, art, and film. From Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) to The Hunger Games (2012), filmmakers have anticipated possible futures ranging from utopias to post-apocalyptic nightmares.

Gattaca (1997, written and directed by Andrew Niccole) is set in the “not too distant future.” Near future science fiction runs the risk of having many of its assumptions already proven wrong and dated in just a few years. It also presents a recognizable future with ideas that we can easily grasp. The technology is familiar and not completely beyond our understanding and the visual cues in the film are all things we are well-acquainted with.

In Gattaca (the title refers to the name of a private space agency – Gattaca Aerospace Corporation), science has advanced to a believable not too distant future – genetic engineering. Congenital disease can, in many cases, be avoided as can characteristics for alcoholism, drug addiction and abusiveness, and intelligence and physical abilities can be maximized. Parents who can pay the price choose to produce these genetically manipulated offspring. This advanced method of procreation creates children who are preferred: they are called “valid.” But some still do it the old fashioned way. And while we may see making babies in the back seat of a Buick as more moral (and a whole lot more religious), the society of Gattaca does not. These children are considered “in-valid.” This difference in identity is one of the main themes of the film.

Life is not kind to in-valids. Their heritage is the lower class of society. They are the laborers, workers, and service people who help make the valid life all the more worth living. This new underclass is not determined by aptitude, ability, or education, and not by race, creed or color; it is determined solely by genetics. The in-valid are on a path that they will not be able to get off. The society of Gattaca has pre-determined who will be the targets of their discrimination, injustice, and poverty.

Despite this – and because of it – there are people who do not passively accept their station in life. And they will risk everything to change it. And in this is the other main theme of the film: the power and the will of the individual. Gattaca is first and foremost an affirmation of perseverance, the human spirit and its survival.

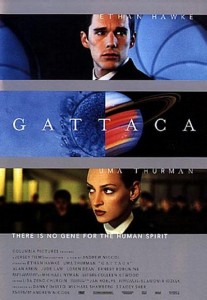

Ethan Hawke in “Gattaca.” © 1997 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Genetic identity is a valued commodity and like most valued commodities it has an accompanying black market. Dealers broker arrangements between in-valids who are willing to risk losing their freedom and valids who are willing to give up their identity. These valids “rent themselves out.” For a price, their hair, skin, blood, urine – their identity – becomes the property of the in-valid. This is what is known as “the borrowed ladder.”

Since the first time he looked into the night sky as a boy, Vincent (Ethan Hawke) has dreamt of becoming an astronaut. As an in-valid, the closest he will come to space is his job as a maintenance worker at Gattaca headquarters. Jerome (Jude Law) is an employee at Gattaca who is on leave from training for a mission after a car accident. A champion swimmer, Jerome could only manage a silver medal in the Olympics. He just wasn’t quite good enough. His subsequent botched suicide attempt has left him in a wheelchair, crippled, bitter, and wanting just to be left alone.

In the cold and impersonal society of Gattaca, nobody knew or noticed Jerome. Nobody will remember his face; his retinal scan and thumb print are his most recognizable features. So the in-valid Vincent becomes the valid Jerome and Jerome, completing his disconnection from society, now calls himself by his middle name – Eugene. Every morning, Vincent/Jerome scrubs away every dead skin cell and hair follicle on his body and Jerome/Eugene prepares urine and blood samples. They apply fingerprints to Vincent’s fingers and use special contact lenses to correct vision and fool the retinal scanner. An implanted pacemaker will mask his irregular heartbeat. Vincent will assume Jerome’s life and take his place on the mission to Titan.

The world of Gattaca is neat, clean, sleek, and modern. Yet it is at the same time sinister. The Gattaca employees appear robot-like as they dress in the same dark suits, wear the same hairstyle, and move in the same restrained, orderly fashion. As in Metropolis, they queue up to go through turnstiles that require a valid fingerprint. It is a society that is obsessed with the identity of its citizens.

A scene from “Gattaca.”

Employees at Gattaca are diligent in exposing suspected in-valids who may have gained access to the space agency. Anyone can have anyone “sequenced” by lab technicians who work from behind a line of windows like bank tellers. A strand of hair from a comb, a fingernail clipping, a bit of saliva (“I just kissed him an hour ago”). Results come back in seconds.

Vincent falls for co-worker Irene (Uma Thurman), even though his feelings for her could jeopardize his plan. Irene, being a true woman of the not too distant future, is a little more cautious and has Vincent sequenced. When he passes the test (she used a strand of hair that Vincent had planted) a romantic relationship begins. And when the truth is discovered, Irene realizes that there is no difference between her and the in-valid Vincent – that he is as good as her or “as good as any of them.” When she doesn’t expose him it is less an act of love than an expression of her humanity, an expression of free will in a society that discourages it.

When the mission director is murdered the week of the launch, the other key character in this film, Vincent’s younger brother Anton (Loren Dean), heads the police investigation. Anton solves the murder and also solves the mystery of the eyelash found at the scene. The eyelash of an unidentified in-valid. An identity that will remain his secret.

As boys, the two tested their strength and courage by swimming out to sea until one of them gave up, having to turn back to shore. Anton always won until they got older when Vincent wins despite his weak heart. The night before Vincent is to leave for Titan the two go on one final swim together. When they have gone too far Anton quits first yelling, “Vincent! How are you doing this Vincent? How have you done any of this? We have to go back.” And Vincent’s reply to Anton is, “You want to know how I did it? This is how I did it Anton: I never saved anything for the swim back.”

Ethan Hawke and Uma Thurman in “Gattaca.” © 1997 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

In the end Vincent leaves Earth aboard a space ship headed for Titan. His overdue heart will keep him from making the return trip. There will be nothing left for the swim back. Eugene, taking a trip of his own, finds the peace he couldn’t find before. And Irene and Anton are less sure of their world having had their lives changed by someone they were told was less than what they were.

The look of Gattaca is remarkable. Beautifully designed, lit and photographed and surprisingly free of special effects, it is a highly stylized film that looks completely futuristic by borrowing elements from the 20th century. The interior architecture from design to furniture, plumbing fixtures, and lights is futuristic enough and whirring turbine engines seem in place in Citroën DS19s and Studebaker Avantis from the 1960s. The scenes at Eugene’s house were filmed at the futuristic CLA Building at Cal Poly Pomona (1993) and the Gattaca Aerospace Corporation’s building is the Marin County Civic Center (1962) by Frank Lloyd Wright, its organic design giving a perfect sense of symmetry to the genetically enhanced inhabitants inside.

Although a box office disappointment in theaters, Gattaca is a favorite among sci-fi fans. Even if you’re not a sci-fi fan you will find it a worthwhile film that is revealing of humanity’s struggle with identity and the will of the individual. It is both an elegy for the destiny of humanity and a celebration of its spirit. As for a future like Gattaca, we may prefer to think that it will never happen, but we know that it is all too possible.