The fall of 1967 found The Beatles feasting on the critical and commercial success of the Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album and looking for a follow-up. Since the record’s June release, the group had become cultural and musical icons and had attained a form of rock sainthood. They were, by all accounts, perceived as infallible.

Then, in early September, just a few weeks after the death of their manager, Brian Epstein (the victim of an accidental overdose of prescription-drugs on August 27, 1967), the Beatles began work on their next project – a film for television entitled Magical Mystery Tour. It would be an extravagant film, every bit as colorful, interesting, and original as their music. Or, at least that was how they envisioned it.

Unfortunately, as Beatles’ producer George Martin explains in Roy Carr’s The Beatles at the Movies (New York: HarperPerennial, 1996), things did not turn out that way and “if the Beatles’ professional career were to be plotted on a graph, Magical Mystery Tour was definitely a dip” (113).

The History

The four Beatles planned to make their new film entirely on their own; free from the studio system, the producers, the directors, or anyone else that might hinder the creative processes or perpetuate the mop top image that their previous movies had ingrained in the public consciousness. It is interesting to note that just prior to the production of Magical Mystery Tour, Walter Shenson (the producer of the two previous Beatle films – A Hard Day’s Night and Help!) had been actively searching for a third film project for the band. Like the group, he had also hoped to find a vehicle wherein the Beatles would not have to play themselves (as they had in their earlier films) but rather, as noted in The Beatles at the Movies, “four characters who look, think and talk like the Beatles but are [in fact] different characters” (92). Distancing themselves from their public image seems to be precisely what the Beatles had in mind for their next film project as well.

Paul McCartney had originally written the “Magical Mystery Tour” song for inclusion on the Sgt. Pepper album. However, when it became clear that the track was not appropriate for that project, it was shelved and quietly forgotten until the Beatles convened in September 1967 to discuss how to proceed with the business of being the Beatles. Having assumed a sort of defacto leadership role within the group following the loss of Epstein, McCartney suggested the musical, fantasy film he had concocted as their next project. “I’m not sure whose idea Magical Mystery Tour was,” he states in The Beatles Anthology (San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books, 2000). “It could have been mine…we were all in on it – but a lot of the material at that time could have been my idea, because I was coming up with a lot of concepts” (120).

The “Magical Mystery Tour” album/soundtrack.

McCartney had developed the basic concept of the film with the help of longtime Beatles’ roadie Mal Evans. The real-world inspiration for Magical Mystery Tour was, of course, Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters who were, according to Philip Norman in Shout! The Beatles in Their Generation (New York: Fireside, 1981), “an American hippy (sic) troupe which, two years earlier had journeyed by bus through the Californian backwoods, buoyed up by LSD diluted into thirst-quenching Kool-Aid” (313). McCartney’s idea for the Beatles’ film was simply to fill a colorful bus with assorted actors, friends, and oddballs (much like the actual Pranksters), ride out to the English countryside, and film whatever happened. As free form as this concept sounds (or may appear upon viewing the final product), the project was in fact partially outlined, to a certain extent at least. “Paul and John [Lennon] sat down in Paul’s place in St. John’s Wood,” recalled Neil Aspinall in The Beatles Anthology. “They drew a circle, and then marked it off like the spokes on a wheel. It was a case of: ‘We can have a song here, and a dream sequence there,’ and so on. They mapped it out” (272). Lennon also remembered plotting the film’s structure: “We knew most of the scenes we wanted to include; but we bent our ideas to fit the people concerned, once we got to know our cast. If somebody wanted to do something we hadn’t planned, they went ahead. If it worked, we kept it in” (272).

However “mapped” out the film’s structure was, the group still had no intention of following any rigid guidelines or “rules” of filmmaking during production. The Beatles hoped that this “organic” approach to the medium would improve upon their previous filmmaking experiences. They planned, according to Philip Norman, to “make a film unhampered by Walter Shenson, Dick Lester, and all the petty restraints which had made Help! and A Hard Day’s Night ultimately [such] tedious and disappointing [experiences for them]. Filmmaking, as they well knew, was easy enough. All you need[ed] was money and cameras, and someone saying, ‘Action!’” (314). However, the final product suggests that it may have been the guidance and expertise that Shenson and Lester provided that had harnessed the Beatles’ talents and irreverent attitudes and characters and had so effectively portrayed them within the confines of the medium (much as George Martin managed to do so well in the recording studio).

The Production

Production of the Beatles’ Magical Mystery Tour began on September 11, 1967, just a few days after the group decided to move forward with the project. Unfortunately, the from-the-hip method of working that the Beatles employed so successfully while making music only resulted in heartache on the film set as there were no watchdogs to help make technical realities of their creative visions. Since they had afforded themselves almost no pre-production time, the shoot was plagued with problems from the onset. Also, the extent of the Beatles’ fame hindered their ability to move about freely with a film cast and crew and they were consistently hounded by the press and fans during filming (a problem not aided by the signage on the bus which blatantly advertised “Magical Mystery Tour” – it might as well have said “Beatles in Bus – Follow”).

The Beatles looking out from the top of the “Magical Mystery Tour” bus (perhaps for possible locations?).

They filmed for five days in a variety of locations, or essentially, wherever the bus stopped. Since nothing had been formally planned in terms of travel arrangements or lodging or anything really, the shoot went far from smooth. Hotels rarely had enough rooms for the cast and crew and feeding the entire production proved almost impossible. The whole undertaking seemed doomed. In fact, as Philip Norman writes, “the Magical Mystery Tour, far from floating off into a psychedelic sunset, labored sluggishly and all too materially around Britain’s summer holiday routes, hounded by a cavalcade of press vehicles, surrounded at every random halt by packs of sightseers and fans. Encountering a sign to Banbury, they followed it, to see if Banbury had a fair. It didn’t, so they turned towards Devon, traffic accumulating in front of them and behind. The police of successive counties looked on, watchfully impassive. The journey, it became quickly evident, held neither magic nor mystery” (314).

After completing location filming, the production was supposed to move to Shepperton Studios to shoot several of the film’s more complicated scenes, which would hopefully stabilize the project. Unfortunately, no one had bothered to book studio time. So, the Beatles were forced to scramble and secure the use of an abandoned US Army Air Force base at West Malling Air Station as a makeshift studio. Additional shoots were required in late-September for an incongruous, self-indulgent scene involving a stripper and the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band as well as a late-October shoot in the South of France for the film’s “Fool on the Hill” sequence. Ultimately, the Beatles amassed over ten hours of footage. During the following eleven weeks this considerable amount of film was edited down to around 50 minutes. By this point the group was plagued by a lot of infighting which resulted in many arguments as to the best way to edit the film. It would not be uncommon for McCartney to edit for half a day only to have Lennon come in later that day and redo all of the work that had been done earlier – not a very efficient way to produce a quality group project. A staggering 90 percent of the footage that they shot was excised; some that perhaps might be of interest to rock historians (including, among others, a scene featuring Traffic performing “Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush”) if it were ever miraculously rediscovered.

The Film

Magical Mystery Tour begins with Ringo Starr (playing a character named Richard Starkey) purchasing tickets for something called a Magical Mystery Tour. Next, Richard and his Aunt Jessie make their way to the tour bus and are introduced to several characters; the most notable of which is Mr. Bloodvessel (who apparently purchases tickets for every trip – he believes he is one of the couriers or tour guides). (His character’s introduction is a subtle reference to the “little old man” exchange from A Hard Day’s Night.) The other passengers on the bus (apart from the courier and hostess – as well as the other three Beatles) are little more than extras in the film. None of them are specifically germane to advancing the story (or whatever there is of one) or given all that much to do other than lurk around in the background.

The cast of “Magical Mystery Tour” riding the tour bus.

After Richard and his Aunt have a bit of a tiff, Paul has a run-in with a rather stuck-up actress and the film launches into its first musical number – “The Fool on the Hill.” The piece is actually a nicely crafted music video apart from a few too many close-ups of Paul crazily darting his eyes back and forth as he “sees the world going ‘round.” The next segment features Victor Spinetti (who was also featured in A Hard Day’s Night as a television producer, and in Help! as a mad scientist) as an unintelligible Army recruitment Sergeant who screams gibberish until the scene bizarrely shifts from an office to a vast field before abruptly cutting to an event called the Magical Mystery Tour Marathon – an homage to It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World which ostensibly serves to unite the tour passengers as they ride the bus to victory (for what it’s worth, Richard/Ringo is driving).

Next, it’s back to the tour bus where the courier instructs his passengers to look out the window where a series of colorized aerial shots of Iceland are shown as the song “Flying” plays. While this scene is both whimsical and rather innovative in its use of color (Stanley Kubrick would employ a similar technique – albeit a bit more effectively – during the final monolith sequence at the end of 2001: A Space Odyssey in early 1968), it is simply boring in black and white (which is precisely how the public first saw it). We are then introduced to the Beatles (along with Mal Evans) playing the four or five magicians who “turn the most ordinary coach trip into a magical mystery tour.” This is the first instance where the humor that the Beatles had been known for in previous films (and in real life) is even remotely evident.

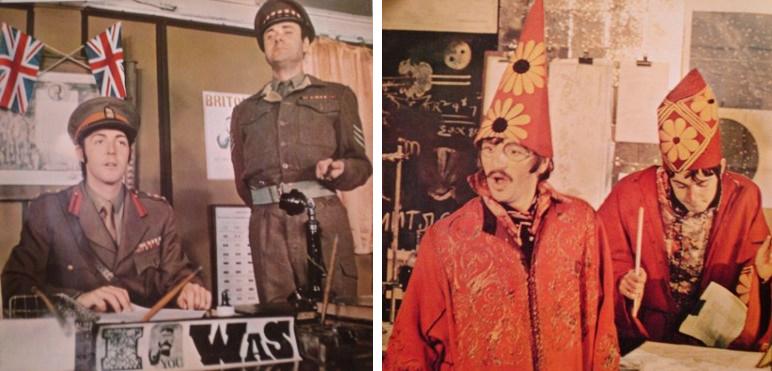

(LEFT) Victor Spinetti (on right) with Paul McCartney and (RIGHT) two (Ringo Starr and Paul McCartney) of the four or five magicians from “Magical Mystery Tour.”

Meanwhile, back on the bus, Mr. Bloodvessel flirts with Aunt Jessie and a pseudo-romantic dream sequence ensues. This earnest, though a bit too long, segment is ended when Bloodvessel begins acting like a courier again. The film then quickly cuts to a video for “I Am the Walrus” complete with dancing eggmen, swaying policemen, and the Beatles themselves dressed in bizarre (yet colorful) animal costumes. Several camera tricks (super-imposition and the use of split screen) make this section noteworthy, although the use of these techniques does seem haphazard and often arbitrary. Indeed, throughout the film, such avant-garde flourishes appear to have been used more for the sake of using them than for any valid cinematic or narrative purpose. It is, as Nicholas Schaffner writes in The Beatles Forever (Harrisburg, PA: Cameron House, 1977), these “gimmicks – lots of slow and fast motion, dizzy zooms in and out of close-up, and superimpositions of images…[that] give the impression of clever kids playing with a new toy” (90).

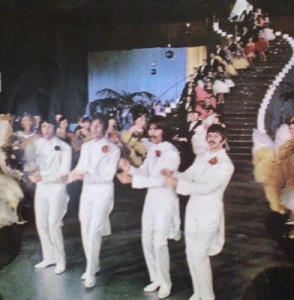

The final moments of the Beatles’ “Magical Mystery Tour” film.

John’s brief, but charming scene with Little Nicola is followed by a disturbing dream sequence that takes place in a restaurant where a waiter, again played by John, feeds Aunt Jessie obscene amounts of muddied spaghetti with a shovel. The scene is both surreal and grotesque and is perhaps one of the real “chances” that the film dares to take. The tour then switches locations to a field where the passengers shuffle into a small tent and inexplicably emerge in a screening room where they are treated to a rather uninspired music video for George’s song “Blue Jay Way.” There is little to this segment other than George sitting cross-legged in a parking lot playing a chalk-drawn keyboard while car headlights beam through a fog-machine produced haze behind him. The few camera tricks that are utilized do not succeed in saving this rather pedestrian effort. The Beatles now reappear as their magician characters to initiate a sing-a-long aboard the bus. An incongruous scene featuring the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band and a stripper follows before the film inexplicably cuts to the Busby Berkleyesque “Your Mother Should Know” finale complete with the Beatles dressed in white tuxedos descending a towering spiral staircase as they perform the song.

The Public and Critical Reaction

The film premiered on December 26, 1967 (Boxing Day) on BBC-1. Unfortunately, since BBC-1 was not equipped to broadcast in color in 1967, the program was seen by an estimated 15 million befuddled viewers in wildly unimpressive black and white. Britons no doubt expected to see a charming holiday musical program from their beloved Beatles (perhaps something more like the promotional film for the song “Hello Goodbye”). Instead, they saw what many called a bizarre, plotless film that, at best, seemed to approximate an acid trip. Most viewers (especially those with a means to make their voice heard) were not amused.

Critical reaction to Magical Mystery Tour was almost universally negative. While viewers had hoped to witness television history, they instead saw what Philip Norman called “a glorified and progressively irritating home movie” (316). Ironically, Richard Lester, had been quoted by Michael Housego in the Daily Sketch on October 19, 1967, as saying that he did not think that the Beatles “should make another film with a professional filmmaker, but [rather should] do it themselves and produce the world’s most expensive home movie” (Carr 118). Whether he had already seen some of the raw footage the Beatles had shot would be pure speculation. But the fact is that Magical Mystery Tour did not satisfy the majority of the television audience when it was first aired. It was, in essence, the Beatles first tangible failure.

An example of the “mop top” image that the Beatles were trying to overcome is evident in this animated Saturday morning cartoon show.

As with their music, the Beatles had intended, according to McCartney in The Beatles Anthology, to “do something different” cinematically and it simply blew up in their faces (120). But making a “safer” film along the lines of their earlier movies or even their previous televised Christmas shows was of no interest to them. They had outgrown the mop top image to which the public and critics alike apparently expected them to adhere. This role-fulfillment is central to the explanation that Lennon gives in The Beatles Anthology for the negative reaction to the film: “[The critics] thought that we were stepping out of our roles. They’d like just to keep us in the cardboard suits that were designed for us. Whatever image they have for themselves, they’re disappointed if we don’t fulfill it. And we never do, so there’s always a lot of [that kind of] disappointment” (274). McCartney’s stance in the London Times article “Beatles reply to TV film critics” which ran on December 28, 1967, was a bit more defensive: “We thought we would not underestimate people and would do something new. It is better being controversial than purely boring” (2). Harrison was more pragmatic with his view in The Beatles Anthology of the criticism aimed at the film: “The press hated it. With all the success that we had, every time something came out…they’d all try to slam it; because once they’ve built you up that high, all they can do is knock you back down again” (274). Due to the tremendous amount of negative press surrounding the film a scheduled airing on American television was cancelled. The BBC did finally rebroadcast the film in color in early January, but the damage to the Beatles’ mystique was irreversible, at least as far as the Magical Mystery Tour film was concerned.

The Music

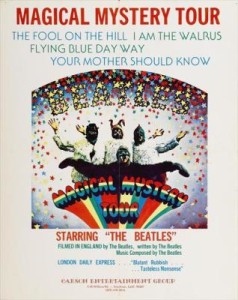

Although the Magical Mystery Tour film met with harsh criticism, the film’s soundtrack fared far better. An album containing the six songs featured in the film (“Magical Mystery Tour,” “The Fool on the Hill,” “Flying,” “Blue Jay Way,” “Your Mother Should Know,” and “I Am the Walrus”) as well as the band’s other 1967 singles (“Hello Goodbye,” “Strawberry Fields Forever,” “Penny Lane,” “Baby You’re A Rich Man,” and “All You Need Is Love”) was released in the United States in November. An EP containing just the film songs was released in Britain the following month. Both releases featured a lavish color booklet including stills and stories from the film, as well as some inventive cartoon depictions of the Beatles in their magician guises.

The music (as well as the packaging) echoed the spirit and inventiveness of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Some critics, writes Mark Wallgren in The Beatles On Record (New York: Fireside, 1982), even claimed “that the songs from the TV special were quite possibly just as good as, if not better in some cases than, the tracks on Sgt. Pepper” (167). Although “Magical Mystery Tour” and “Your Mother Should Know” are little more than retreads of Paul’s far superior “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” and “When I’m Sixty-Four,” “The Fool on the Hill” is arguably one of the finer songs he has ever written. Indeed, the album also features one of the denser and more complicated Lennon compositions in “I Am the Walrus.” While Sgt. Pepper was a colossal achievement as a whole, the music of Magical Mystery Tour more than ably holds its own place within the Beatle canon when put up against the group’s other seminal albums.

The Aftermath

Over the years, the Magical Mystery Tour film has achieved cult status among Beatle fans (particularly in America). In fact, it wasn’t until the mid-1970s when the film began showing up at Beatle fan conventions and the occasional “midnight movie” house that many fans got their first look at the film. It was during this period of rediscovery that the film began earning a reputation as an “art” film. Perhaps his opinions are obscured by the blinders of hindsight, but McCartney has claimed that the Beatles had always intended Magical Mystery Tour to be viewed as “an art film rather than a proper film” (The Beatles Anthology 274). He has even alleged that director Steven Spielberg claims to have studied Magical Mystery Tour while in school. The avant-garde persona the film has taken on in the years since its release probably has more to do with perpetuating the Beatles mythos than with the actual critical worth of the film or its place within cinematic history. Still, several techniques and tricks used in the film (quick edits, for example, though chaotic and undisciplined, were ahead of their time) did showcase the Beatles’ penchant for bending the established rules set before them. However, as Judson Knight points out in Abbey Road to Zapple Records: A Beatles Encyclopedia (Dallas, TX: Taylor Publishing Company, 1999), while the Beatles “must have figured that, just as they’d broken all the rules in the studio, they could do the same behind the camera. The critical difference, however, was that they knew the rules of music before breaking them” (153).

The Beatles performing the song “I Am the Walrus” in “Magical Mystery Tour.”

Probably the most enduring quality of Magical Mystery Tour is that it was the first real attempt by artists to produce their own music videos (the art form itself being something that the group pioneered in A Hard Day’s Night and Help!). McCartney continually cites the film’s music as the primary reason for its importance (he is particularly fond of the fact that it is the only way to see a performance of “I Am the Walrus”). Starr, however, takes a more simplistic approach to the film and the initial negativity associated with it: “It was really slated but, of course, when people started seeing it in colour they realised that it was a lot of fun. In a weird way, I certainly feel it stood the test of time” (The Beatles Anthology 274).

While Magical Mystery Tour has endured a less than complimentary history, it has maintained an important place in the larger Beatle canon. It is routinely sought out as something that every Beatle fan should see and has garnered a place in history of cinema as a film of some measurable amount of importance (if not artistically, at the very least historically). Whether they were aware of it or not, the Beatles managed to capture a specific moment in time with the film or, more appropriately, a specific perception of a moment in time. By adopting the Merry Prankster concept, McCartney and his band mates had unwittingly stumbled onto a microcosm of a major aspect of the sixties – the pursuit of freedom (though not in any sort of patriotic sense). As Derek Taylor wrote in It Was Twenty Years Ago Today (New York: Fireside, 1987): “[Ken] Kesey, with the true frontier mentality, was all for pushing forward, getting on the road and taking the high ground wherever the challenge seemed worth the trouble. The importance of breaking down rigid forms was never questioned. Like [Allen] Ginsberg, he was for letting the trip take the traveler where it would” (96). Magical Mystery Tour was/is, in essence, just such a “trip.”

Or, perhaps it is as Laurence Marcus and Stephen R. Hulse observed in their review of the film (December 7, 2003), Magical Mystery Tour is “an echo of a more simplistic and child-like decade.” Unfortunately the Beatles never recognized it as such or just tired of the project, and were unable to embrace it as wholly as they did their music. In fact, Henry Raynor, of the London Times, called the film “a programme to experience rather than to understand” when it first aired in his review entitled “Beatles’ anarchic mystery” (December 27, 1967: 11). Maybe if the Beatles had explored the concept to its fullest potential, then they might have succeeded despite their failure.

Cookware sets

I’d hardly call MMT a “tragedy.” The Beatles were experimenting like crazy, in all areas, and this project just fell a bit flat. So what? They living 5 years for every 1, and much of the music from Mystery Tour still endures.

Al

I watched this on magic mushroom, and it made perfect sense. So there you go.

Tthadman

Me thinks the biggest tragedy is the fact that it was shown in B&W on British TV when color was so central to its concept.

Also, the copies that have been released over the years are very scratched.

samofson

The music on the album is some of their best. As for the film, when you compare it to most MTV videos, it set the trend and is comparable to most. However, I don’t care for MTV videos.

Machi

Brian’s Accidental Overdose? mmmhhh…This is the first time ever I read about the suicide been treated like an accident…U r changing history. Don’t.

Mike Tyrkus

Actually, I believe it’s generally accepted that it was in fact an accidental overdose (a quick internet search will bring up a handful of sources that site it as such). There’s no doubt Brian more than likely suffered from depression and such a tragic end to his life might have been inevitable. However, when the authorities of the time ruled it an accidental overdose and most, if not all, of the biographies written since call it such, I’m willing to side with the court of popular opinion on this issue. Perhaps you might just need to read a little more.

Ivan

Critics still have precious little to write about the Beatles that isn’t more or less tearing them down. I have always seen this essentially as an artifact of mediocrity attempting to analyze actual superior creativity, and it always plays as somewhat inappropriate in the case of the Beatles. I think that, more than almost any other pop/rock group, the Beatles solidly deserved their great fame due to the overall originality and exceptionally high quality of their works. But critics’ job is to be critical even when there’s not much to criticize and so, unfortunately, the vast majority of negative criticisms of the Beatles almost always play as grasping at straws. Magical Mystery Tour is not a “great film” but it very obviously doesn’t try to be! It is simply some very credible accomplished artists having fun making a fancy experimental home movie as stated. If they wanted to make a great film they were certainly smart and wealthy enough to hire serious filmmakers and screenwriters (and they were the personal friends of several), but it is utterly obvious that that is not what they were doing with MMT. To criticize it as anything but their fun, expensive, experimental “home movie” simply betrays ineptitude on the part of the critic.

Wordsworth_from_Wadsworth

As the 2012 PBS “Great Performances” showing of a BBC documentary on “Magical Mystery Tour” noted, Brian Epstein participated in the planning of the film,and was “quite enthusiastic about it.” Epstein died before filming started. Work on “Magical Mystery Tour” had begun while Epstein was alive, and thus this article is in error. His presence may have refined the final product. With a tad more planning, scripting and coherence, this would have been an art film for the ages. Of course, the music is wonderful by itself.

McCartney compares “Magical Mystery Tour” in a small way to Buñuel’s “Un Chien Andalou,” While watching another Buñuel-Salvador Dalí film, “L’Age d’Or,” I found myself enjoying the experience more while listening to the commentary. Likewise, “Magical Mystery” is enhanced by the documentary noting its place in history, with the ascent of the Beatles from the underground out of the privations of WWll.

McCartney and the other lads needed an Epstein or a cinematic George Martin to shape and edit their ideas, without taking away from their seminal, epochal creativity. Nonetheless, as several coevals of the Beatles said on the documentary, “I loved it and thought it was brilliant.” “Magical Mystery Tour” was a wonderful, magical farce.

Devon L Smith

“The Tragical Misery Tour” As some have called it …I had watched it on a video I happened to actually rent from Blockbuster video when they were still around and it was a totally mishmash of terrible filming~ After all the years I was curious why it was a bad film , AND I WAS ANXIOUS TO SEE IT, It was an experimental flop and The Album was way better alone than the film was. Whom ever kept the film from the USA did themselves a favor for the Beatles…One might as well say an amateur project of what or where do we go from here ? Crazy enough not many Beatle musicians ever did well in movies to this day after HELP or A HARD DAYS NIGHT…not even CAVEMAN movie cult with Ringo Starr[ Supposing where he met wife Barbara Bach] did get any rave reviews…it just wasn’t their moment in time to be . I still find delight in that album MAGICAL MYSTERY TOUR..sounds great in stereo to this day. Some things were just meant to be.