In 1963, Italian horror director Mario Bava made his last black and white film. The Girl Who Knew Too Much heralded the arrival of a film genre that would have a prominent place in cinema until the mid-1970s and is still popular today – giallo.

A sub-genre of the mystery/thriller/crime story and a cross-over from horror, giallo had its roots in the American and English mystery novels of the early twentieth century. The works of mystery writers Edgar Allan Poe, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Agatha Christie, and American detective writers James M. Cain, Dashiell Hammett, and Raymond Chandler began being published in Italy in 1929. These novels were printed on cheap paper and always bound with a yellow (giallo) cover. They introduced a view of society which was very contrary to modern Italian fiction in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Italian authors were influenced and began writing mysteries of their own, usually under an English sounding nom de plume. While the public saw these novels as entertainment intellectuals and critics called the giallo vulgar, unnatural, and foreign to Italian culture. They were actually banned by Mussolini for being subversive but came back after the end of WWII. Reflecting the post-war mood of the country, the public fully embraced the giallo as well as other non-classical literary and film genres as Italy became part of the new post-war Europe.

Though gialli are considered by some a horror sub genre, this is not entirely accurate. There are no vampires, witches, monsters, or ghosts. There is no supernatural element or unexplainable phenomenon. Rather than gothic, the settings are modern, international, and fully reflective of Italy’s desire to turn the page from its past. But what the gialli do have in common with horror are the brutal and bloody murders. And while there can be no discounting the importance of the elements of suspense and mystery to the giallo, it is their violent murders that are its essence.

The murders are usually done with a knife or straight razor (never a gun) exploiting a common experience of pain with the audience. While few of us have been shot, all of us have cut ourselves with a knife or a piece of glass, a familiarity that makes slashers so cringe worthy. The victims are usually beautiful young women. And, of course, there is little sense in slashing a beautiful young woman if she’s not less than fully clothed. The importance of this detail to giallo couldn’t be made clearer than by the lurid title of Andrea Bianchi’s 1975 film: Strip Nude for Your Killer.

But don’t bother accusing gialli of misogyny. That would be pointless as this is a strong part of the allure of these films. Women are generally portrayed as anywhere between needing the help of an analyst and being psychotic murderers themselves. While giallo does have it’s version of the film noir “good girl,” women are definitely second-class citizens. They are high class and bored at best, or unrepentant killers at worst. They are adulterers or are driven by greed. They are no good and are deserving of their fate.

A key element of giallo is the central role of the eyewitness. Someone sees, or thinks they see, a murder. This visual uncertainty or mistaken identity is found in almost all gialli. The “eye” also becomes part of the cinematic experience as directors often employ point of view shots from the “killer-cam,” fast zooms to the victim, and claustrophobic close-ups of the killer’s eye. And that is the best look we get of the killer who is dressed in black hat, trench coat, and stocking mask. As he slashes his victim we see only the gloved hand – and the knife.

The eyewitness as the central character sets up another Hitchcockian device – the everyday person caught up in the extraordinary circumstance. Gialli focuses on the investigation by the amateur sleuth who does what the ineffectual police are incapable of – a characterization of law enforcement borrowed from Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes mysteries. These amateur investigators are often a man and woman team who, having been thrown together by the circumstances of the murder, set out to solve the mystery. But it’s not easy as the stories are littered with red herrings – another key element of the giallo. As if that’s not enough, the plots are overly complicated, bordering on incomprehensible. But trying to figure out the identity of the killer is part of what makes them so enjoyable.

Technically, the films are beautifully made with outstanding cinematography, color, camera direction, set design, and locations. The musical scores are usually well done and the visual cues are striking: continental fashion, sports cars, modern architecture and interior design, Scotch whisky, and assassins dressed in black. And, of course, beautiful women.

There were over one hundred gialli made during the Golden Age of giallo which ended around 1975. Here, Cinema Nerdz presents a brief overview of ten of the greatest works by the leading auteurs of the genre. Whether you are new or familiar to the genre, here is list of films for your enjoyment.

____________________________________________________________

1. The Girl Who Knew Too Much, Mario Bava (1963)

The title alone lets you know what Bava thought of Hitchcock making a clear reference to Hitch’s The Man Who Knew Too Much. The film also makes a clear reference to giallo literature: on the plane from America to Italy in the opening scene, the protagonist, Nora Davis, is reading a yellow covered paperback entitled The Knife. While staying with her aunt in Rome, Nora sees a woman with a knife in her back being dragged away from the scene by a man dressed in black. Again the giallo uses one of its favorite devices – mistaken identity and misinterpretation of what is seen. Bava also introduces the red herrings, amateur investigators and the psychotic murderer. This would be Bava’s last film shot in black and white and is photographed in the Hollywood film noir style of expressionist, chiaroscuro lighting.

2. Blood and Black Lace, Mario Bava (1964)

Bava further defines the genre in his second giallo. The Italian title translates literally as “six women for the murderer,” which indicates another important giallo convention: a high body count. Drug dealing, blackmail, and murder take place in and around an haute couture fashion salon filled with beautiful models who are brutally murdered one by one in a variety of ways. All by a murderer in black fedora, jumpsuit, and gloves – the outfit that became de rigueur in future gialli. The vibrant Technicolor was beautifully lit with lots of primary colors – especially red.

3. Bay of Blood, Mario Bava (1971)

Also known as Twitch of the Death Nerve, this one sets the stage for the Hollywood slasher films of the 1980s. The body count is high, the death scenes very inventive (slashing, hanging, decapitation, impalement), and the plot complicated beyond recognition. Friday the 13th is basically a remake of this one with some of the death scenes lifted frame for frame. The motivation for the murders is once again greed as several people fight for control of a valuable piece of real estate on a beautiful bay.

4. The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, Dario Argento (1970)

Argento’s first film did something Bava’s gialli didn’t: it became an international hit. This film established giallo as a box office phenomenon and soon other Italian directors were jumping on the bandwagon. An American in Rome witnesses an attempted murder in an art gallery. The protagonist then becomes an amateur crime solver when the police are, as always, ineffective. The cat and mouse game is on as the killer stays one step ahead of his pursuer. Argento builds great suspense, dangles numerous red herrings, and surprises the audience with the unmasking of the killer. The murder scenes are both subtle and brutal: blood spatter on the wall, and a gruesome murder with a straight razor that were later lifted almost frame for frame by Brian De Palma in Dressed to Kill.

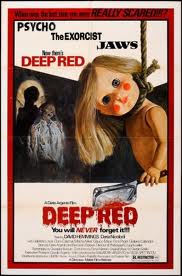

5. Deep Red, Dario Argento (1975)

David Hemmings plays an English musician living in Rome. He witnesses a murder then sets out to solve the mystery (Hemmings has done this before in Antonioni’s Blow Up). He teams up with a feisty female reporter played by Daria Nicolodi (who would become Argento’s long-time partner and mother of daughter Asia). This one features another Argento favorite – death by broken glass. The camera is always moving in Argento’s films and it follows Hemmings as he becomes both a suspect and a target. The plot is nearly incomprehensible – another Argento trademark. And he trades in the usual jazzy, giallo style soundtrack for one by Italian rock group (I didn’t know there was such a thing) Goblin.

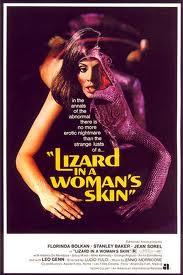

6. A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin, Lucio Fulci (1977)

Like Bava and Argento, Fulci made violent horror films as well as violent thrillers. Dream sequences, drug use, lesbianism, blackmail and murder highlight a complicated but intriguing plot that takes place in a wealthy area of London. In a departure from most gialli, Scotland Yard gets involved and actually solves the case. Carol has a bizarre dream in which she kills her lover Julia. But the dream is reality and Carol uses her psychoanalyst to try to build a defense if she is found out. The eyewitnesses to the crime are hippies stoned on LSD – another obscured view by unreliable observers. This film is beautifully photographed with surrealistic dream sequences that would make even Fellini proud.

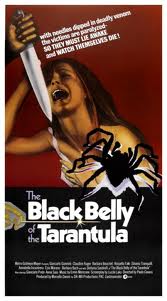

7. The Black Belly of the Tarantula, Paolo Cavara (1971)

Another of the rare giallo that actually portrays the police as competent. The psychotic murderer in this one is well attired in a hat, coat, and flesh colored rubber gloves as the camera focuses on the killers hand in the murder set pieces. The killer has extracted the poison from a wasp that paralyzes its prey (the tarantula). The killer injects the drug and the paralyzed, but conscious women are forced to watch as they are slashed to death – eyewitnesses to their own murders. Cavara’s camera lingers – maybe a little too long – on the naked bodies of the women who die with their eyes wide open. The killings are gruesome, there are three Bond Girls in the cast and the soundtrack is by Ennio Morricone, the leading composer of giallo soundtracks.

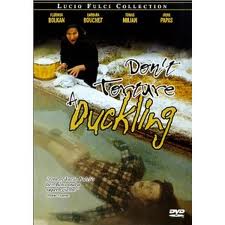

8. Don’t Torture a Duckling, Lucio Fulci (1972)

Fulci’s career was steeped in controversy and in this one goes where few have, then or now. The serial murder of young children is a subject that would make most a bit squeamish but Fulci takes the plunge into the abyss. He does, however, wisely avoid any graphic depiction of violence toward the children. He saves that for the brutal murder of a woman (of course) that is very well done. Fulci exhibits the typical giallo fascination with beautiful naked women, but shocks and offends some as Patrizia, played by Barbara Bouchet, preens naked for a twelve-year-old boy. As usual there are several red herrings but Fulci trades in the cosmopolitan setting for a small village in southern Italy. Fulci also takes a shot at one of the gialli favorite whipping boys: the Catholic Church. Several gialli show contempt for the Church and a few even feature priests (and cross dressing nuns) as killers. Italian censors were not pleased with this film.

9. The House with Laughing Windows, Pupi Avati (1976)

Featuring an all Italian cast (which eliminates the annoying dubbing done for most gialli), this film takes another stab at the Catholic Church. While low in body count and blood, this very good giallo maximizes mystery and suspense. An isolated and secretive Italian village is the setting as a painter arrives in town to restore a church fresco. His work reveals a painting with a graphic depiction of violent death. The code of silence in the town adds to the mystery as our protagonist tries to uncover the secrets of the painting – and the town itself. Who are the figures in the painting? What happened to the artist? What became of the two sisters that he shared an unnatural bond with? And this one has an ending you’ll never see coming.

10. Strip Nude for Your Killer, Andrea Bianchi (1975)

The graphic violence and nudity that made giallo popular abroad was on full display in this extreme film made at the end of the Golden Age of giallo. Crossing the line into sexploitation, if not soft core, this is in the grand tradition of cinematic excess which is a hallmark of giallo. A botched abortion leads to a series of revenge killings at one of the favorite sets of the gialli: a high fashion modeling agency. The killer goes beyond the usual gloved handed assassin by wearing yellow motorcycle leathers and helmet. This one stars giallo queen Edwige Feneche who reprises her role of a sexy young thing that can’t keep her shirt on. Over the top but lots of fun.

bobby

quentin tarantino should make a giallo. he is the perfect director for a new giallo film, its obvious his films are inspired by italian melodrama

Noetic_Hatter

Great list!

This an old post, but I just happened to notice that some of these descriptions contain some pretty hefty spoilers. You might want to consider your text, so that it doesn’t give away the plot twists that are so important in Giallo films. Especially:

A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin