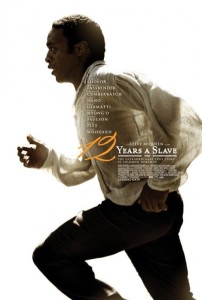

| Release Date: | October 25th, 2013 |

| Starring: | Chiwetel Ejiofor, Michael Fassbender, Brad Pitt, Benedict Cumberbatch, Paul Giamatti, Sarah Paulson |

| User Rating: | |

| Writer: | John Ridley |

| MPAA Rating: | R |

| Director: | Steve McQueen |

On first encountering the 1853 memoir of Solomon Northup, a free black man drugged and kidnapped from an educated, domestic life by opportunistic slave-traders in Washington D.C., director Steve McQueen felt he had read the “[American version of the Anne Frank story]” – two historical people fated to represent institutionalized evils through very personal words and experiences. Northup, as embodied by Chiwetel Ejiofor with a complex psychological palette of dignity, fear, shame, resilient guile, and churning pain, leads us through the true events he experienced in the blighted, grotesque era of Antebellum Southern human exploitation in the unflinching British drama 12 Years a Slave. Terrifyingly objective in detailing the debasing methods particular to the racially-stoked brand of American slavery, 12 Years a Slave is a wearying, enthralling film that is certain to resonate and educate while still being as rivetingly conspiratorial with the viewer as any of the best prison escape adventures.

If the movie was not so inviting to look at, I am certain that McQueen’s characteristic insistence on graphic realism at the end of the film’s numerous whips, bats, hands and nooses would be an impossible pill for many to swallow; plenty will still refuse their medicine as the subject is too grim for entertainment seekers instinctively fleeing from anything troubling. But, suffice to say that no film has plumbed the gory sadism of petty slave-traders as effectively as 12 Years a Slave (a punishingly unbroken take of Solomon near-hanged – gasping for air, with no one coming to his aid as the plantation workers maintain their forced neutrality – is a masterpiece of gut-churning suspense).

The tragic story told in Northup’s published memoir is of an educated black man, with wife and children in New York state, mercilessly duped by men he believed wished to hire his services as a violin player for their travelling circus (that’s Taran Killam from Saturday Night Live impressing as the creepy fop lulling Solomon into unconsciousness). Lured from his home state to the slave-trading ports of Maryland, Northup is shackled within miles of the Capitol building; we feel and share his dawning confusion, terror, and righteous anger at finding himself the captive of slave-traders shipping off to the Deep South. Ejiofor’s Solomon is a cultivated family man with a deep, formal vocabulary – an ideal guide for modern audiences in that Northup’s story is of a resilient Northerner cunningly staying alive to meet his redemption day rather than familiar film accounts of earlier generations of African captives (Roots being the dominant text for decades) without the benefit of Solomon’s wisdom about what awaited the free man (he cannot even bear to hear one of the mother’s impotent wailings for her lost children and risks giving off a snobby detachment from the rest of his brethren). It is to their credit that McQueen and writer John Ridley insist on portraying Solomon as neither saintly redeemer nor revolutionary amidst all of the other more obviously ugly, flawed characters.

Ejiofor’s performance is bookended by Michael Fassbender’s snarling-then-seducing take on the sadistic Master Epps – pushing his inherent likability limits once more for a favored director, Fassbender finds the human conflict inside a corrupted man quoting from his own perverted “scripture.” The psychosexual melodramatics surrounding Epps’ mistress Patsey and his stern wife – a Lady Macbeth in Southern belle finery (Sarah Paulson) – add an element of gothic horror (Mistress Epps inspecting half-nude servants in her lavish dining room; insisting on the vicious lashing Patsey endures in a climactic, gruesome centerpiece).

12 Years a Slave also offers opportunities for distracting appearances from Paul Giamatti as a noxious auctioneer like something out of Pasolini’s Salo; Paul Dano (There Will be Blood [2007]) playing to his limits as a snotty slave-baiter; Alfre Woodard as Master Epps’ brainwashed former mistress; and 12 Years a Slave producer Brad Pitt as Brad Pitt playing an abolitionist carpenter aiding in Solomon’s salvation (“Slavery is wrong,” he declares obviously).

Don’t expect a rote middle school history lesson from 12 Years a Slave; the time has gone for tepid historical back-patting and the only respectable thing to do is to take a series of facts and bring the humanity of it into sharp focus with candid filmic storytelling, something director Steve McQueen has accomplished in this new modern classic.[box_info]WHERE TO WATCH (powered by JustWatch)

[/box_info]