For a film whose villains are obsessed with sensual exploration and obliterating the boundaries between pain and pleasure, David Bruckner’s Hellraiser feels oddly antiseptic.

Don’t get me wrong: there’s plenty of carnage to earn its “R” rating, along with creature designs that are the stuff of nightmares. But where Clive Barker’s original film felt grimy and transgressive, Bruckner’s handling finds nothing beyond the gore. It’s so focused on ripping off skin it never truly burrows under it.

Not exactly a remake of Barker’s 1987 film so much as another story set in its world, Bruckner’s film focuses on Riley (Odessa A’Zion), a young woman and recovering addict who lives with her brother and his boyfriend as she attempts her recovery. They worry that her path to healing might be damaged by her relationship with Trevor (Drew Starkey), a man she met in her 12-step program.

Trevor doesn’t ask Riley to relapse, but he does coax her into breaking into a warehouse to steal a mysterious puzzle box. When Riley inadvertently solves the puzzle, she unleashes a team of mysterious beings known as Cenobites who get pleasure in dishing out pain. The Cenobites abduct Riley’s brother and she sets out to get him back, venturing to a mysterious mansion and drawing her friends into the danger.

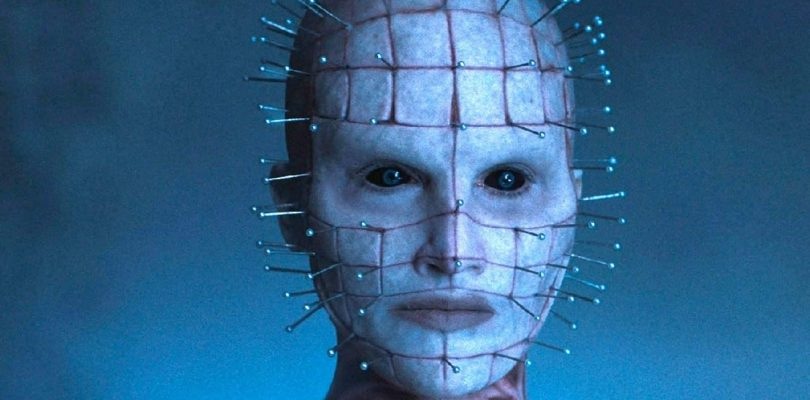

The original Hellraiser’s most enduring contribution to the horror canon was the Cenobite Pinhead, which proved an iconic enough creation to be the focal point of nine movies of quickly declining quality. The big success of this reboot is that Jamie Clayton proves herself a worthy successor to Doug Bradley. Her take on Pinhead is threatening and calm, a sinister smirk always at the edge of her mouth. The film wisely keeps Clayton off screen for much of the film, and then reveals her Pinhead halfway through, and she becomes its most interesting and haunting figure.

Bruckner, the director of The Night House (2020) and The Ritual (2017), delivers some visually disconcerting designs for the Cenobites. They saunter in quietly, their mangled flesh and sinew serving as clothing. One creature has its face obscured by a leather cover and is heard gasping for air; another reimagined version of one of the first film’s most memorable threats has giant bared teeth that snap shut with a nauseating click. When they kill, they use a variety of chains, needles and other nasty implements to puncture, rip and spill gallons of (digital) blood. Bruckner has a knack for mood, and one set piece in a moving vehicle is effectively surreal.

Jamie Clayton in “Hellraiser.” Photo by Spyglass Media Group/Courtesy of Spyglass Media Group – © Spyglass Media Group, LLC 2022. All Rights Reserved.

But none of it is particularly scary. The attempts to weave Barker’s ideas of pushing sensory boundaries in with an addiction narrative make sense, but the film never does much with it. A’Zion is sympathetic as Riley, but the film never successfully ties in her substance abuse with the compulsion of solving a puzzle box or the desperation to sacrifice friends to gain illicit pleasures. Instead, Riley takes some pills at the beginning, regrets it and goes on a quest to get her brother back, with the film never even attempting to create a parallel between Cenobites’ addiction with pain and pleasure and Riley’s own turmoil. The script instead leans on the hoary technique of Riley’s addiction making her untrustworthy, and her claims of demonic visions turning her into the Girl Who Cried Wolf, which is undone quickly after when her friends see the horrific sites waiting for them. By the mid-way point, the film is just another slasher flick, albeit one with several slashers who like to take their time.

The kills are graphic, but the supporting characters are never fleshed out enough for their deaths to provoke much of an emotional response beyond “that’s a shame.” Riley has the most complexity, but the others are paper-thin, which doesn’t lend any resonance when we spend several minutes watching them suffer. And while the film’s final hour pays off the deliberate first half with some visually remarkable sequences, it also plops the characters in a booby-trapped mansion with an obsessive captor (Goran Visnjic) for a stretch that feels straight out of a 1990s direct-to-video horror flick.

Fans of Barker’s original will likely find the increased focus on the Cenobites and their mythology to be a welcome addition to this reboot, and Bruckner creates a film that is visually engaging and atmospheric enough to hold interest. It will likely launch a franchise, but one based on the visual appeal of its villains, not the hook of its story. In the end, Hellraiser is a good-looking little movie, but it delivers neither pleasure nor pain.

| Producer: | Clive Barker, David S. Goyer, Keith Levine, Marc Toberoff |

| Release Date: | October 7, 2022 (on Hulu) |

| Running Time: | 121 minutes |

| Starring: | Jamie Clayton, Goran Visnjic, Odessa A'Zion, Hiam Abbass, Brandon Flynn, Drew Starkey, Adam Faison, Aoife Hinds, Selina Lo |

| User Rating: | |

| Writer: | Ben Collins, Luke Piotrowski, David S. Goyer |

| MPAA Rating: | R (for strong bloody horror violence and gore, language throughout, some sexual content and brief graphic nudity) |

| Director: | David Bruckner |

| Distributor: | Hulu |