| Release Date: | March 23rd, 2012 in the Metro-Detroit area |

| Starring: | Robert Wieckiewicz, Kinga Preis, Benno Fürmann, Agnieszka Grochowska, Maria Schrader, Herbert Knaup, Marcin Bosak |

| User Rating: | |

| Writer: | David F. Shamoon |

| MPAA Rating: | R |

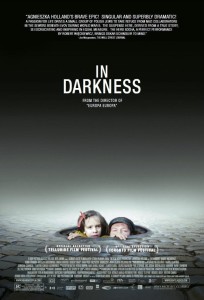

| Director: | Agnieszka Holland |

Enduring sixteen months sequestered in the tunnels underneath the Polish city of Lvov in the last year of the war, a group of Jewish people are aided in their plight by the petty thief Leopold Socha (Robert Wieckiewicz) – an astonishing real life anecdote told at length and with a softened edge by director Agnieszka Holland. Holland has approached Nazi-fooling material before in the much better picture Europa Europa (1990), in which a Jewish youth lives among his persecutors as one of them and falls for Julie Delpy’s Aryan sympathizer. In Darkness is a crowd pleaser for sure, but one lacking the justifiable outrage of the best Occupation and Holocaust films, dancing perilously close to offensive kitsch in moments of sentimental pandering (a superfluous scene of childbirth in the underground tunnels, a concentration camp band playing the “Blue Danube Waltz,” or an erotic interlude shot with soft-core lighting as the sewer drippings pour down on the entwined lovers). I’m far from cynical, but that last one drew out an audible and deeply inappropriate giggle.

Happily, most of the movie centers on the efforts of Socha (the most interesting character in a generous cast) to keep “his Jews” from harm, including the humorous wool-pulling he must do with his good friend in the Polish police force working as a Nazi stooge for profit. Reminiscent of the great French icon Jean Gabin or a young Donald Pleasance, the hangdog Wieckiewicz as Socha has a magnetic presence to draw our eye away from the more rote aspects of the plot and the slick commercial-mindedness of Holland’s filmmaking (she seems to be thinking more about accolades and not offending general audiences more than the bitter truths of the Jewish people’s deprivation). The film falters when he is not on-screen and truly comes alive when he returns to his dowdy, pleasant wife (Kinga Preis) with whom he shares a refreshing camaraderie whether in conversation or in the sort of earthy lovemaking that opens the picture. If only the whole film were as believable and considered as their relationship.

Back in the tunnels, petty jealousies and melodramas play out amongst the huddled families with little consequence (barring the disappearance of one woman which leads to a rescue mission inside a concentration camp). Their tenacious survival efforts take on a prison escape movie urgency interrupted too often by the concurrent plots going on above. At its most involving, In Darkness shows flashes of tension borrowed from great escape flicks like Le Trou (1960)and La grand illusion (1937). Unfortunately, Holland does not go in for grit as much as she does emotional flailing coupled with meticulous art direction that make it appear as if the reptilian stone walls of the tunnels have been freshly scrubbed each day; this attention to aesthetic perfection robs the film of the greater soulfulness inherent in this grim situation lived out by actual people. While admirable in its attempt to relate an untapped, inspiring corner of historical resilience, In Darkness resists delving into its subject with candor and cannot hold up to the profundity of a cinematic tradition which has produced Alain Resnais’ Night and Fog, Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah, Roman Polanski’s The Pianist, and of course Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List.[box_info]WHERE TO WATCH (powered by JustWatch)

[/box_info]