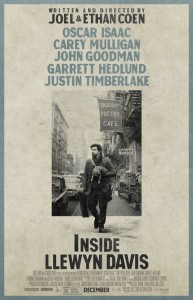

| Release Date: | December 20th, 2013 |

| Starring: | Oscar Isaac, Carey Mulligan, Justin Timberlake, Ethan Phillips, Robin Bartlett, Max Casella, Jerry Grayson, John Goodman, Garrett Hedlund |

| User Rating: | |

| Writer: | Ethan Coen, Joel Coen |

| MPAA Rating: | R |

| Director: | Ethan Coen, Joel Coen |

In scenes organized like the complimentary songs of a weary 2:00 am vinyl album, Joel and Ethan Coen’s Inside Llewyn Davis unfolds as another of their heartfelt, seriocomic, unsentimental, fine-brush portraits of distinctly-Jewish men at an existential dead-end (Barton Fink, A Serious Man) – this time set amidst the grey dawn of the early Sixties boom in the Greenwich Village of folk clubs, earnestness, posing, engaged intellectualism, promiscuity, and artistic exploration. Bearded youths chasing Truth and Poetry, living underground lives in bustling subways and cafes; embittered Trotsky-ites against capitalism with conflicted fame aspirations – Inside Llewyn Davis is the minor-key, muted flip side to the sunny single that many prefer to hear about this era, told with a blend of affectionate black comedy and lamentation for America’s youthful years and directed with masterful refinement by the legendary Coens.

True to form, the Coen’s write around the familiar, leaving the resolution of plot lines off-screen, and keep music performances organic, awkward, and impassioned (even if Burnett’s modern take on the overproduced songs are more Mumford than Guthrie, most of the tunes resonate). “Farewell” is the refrain in more than one of the songs; the young people shot like tarnished angels with baby faces and adult concerns. Details are left to the liner-note obsessives (comparisons and divergences to the actual anecdotes and touchstones of folk legend Dave Van Ronk as told in his book The Mayor of MacDougal Street are there for the perusal).

Oscar Isaac is tasked to convince us that Llewyn is the genuine article: a raw talent reticent to offer his gift to the moment in 1961 when groups like The Weavers or Peter, Paul, and Mary were hitting pop charts with antique tunes [Llewyn misses his chance to join friends Jean (Carey Mulligan) and Jim (Justin Timberlake) in a similar trio]. Llewyn is combative, leftist, impolite, and likely the most gifted of his peers (until that harmonica-wielding boy genius takes the spotlight). Isaac sells this difficult main character with a plaintive quality in his searching eyes and endearing neurosis over a neighbor’s lost cat left in his charge. A dinner party outburst at his academic, counterculture-tourist neighbors and the scene when Llewyn is lured into recording a novelty space-race song at Columbia are hugely comic if you share the Coen’s smartly-aggressive brand of funny.

Nowhere is their peculiar humor more in evidence than the long sequence when Llewyn is given a lift to Chicago to audition for his big break by a gregarious jazzman and his near-mute rent-boy driver (Garrett Hedlund). Though craggy-voiced these days, John Goodman still gives full bluster to the showcase role of Roland Turner, a backseat raconteur making sweeping denouncements of folk music with avuncular wit and fey campiness who ends the ride as a haunting, smack-addicted caution against starving artistry. That section of the film is when you might start considering Inside Llewyn Davis one of this year’s most soulful, unexpected greats (or think it all so aimless and trope-defying for commercial sensibilities).

In their recent work, the Coen brothers have softened their philosophy and made increasingly-slower films with less flash and loads of ego-free confidence. Inside Llewyn Davis is another carefully-curated archive for those looking for the rare movies that still exist in a timeless communal space, told in an ever-deepening round like the best kind of deathless folk song.[box_info]WHERE TO WATCH (powered by JustWatch)

[/box_info]