Martin Scorsese delivers another late-period masterpiece with Killers of the Flower Moon, an American tragedy that proves once again that no filmmaker is better at examining crime, guilt and greed, and the ways they are intimately woven into America’s DNA.

Based on David Grann’s best-selling nonfiction book, the movie tells the story of the Osage tribe, whose members were made rich after being relocated to Oklahoma land atop vast oil reserves. As the film begins, Scorsese captures Osage members jetting around town in fancy clothes and sleek cars while their white neighbors hustle to get some cash by taking their picture, selling tires or begging for a loan.

Into town comes Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio), a WWI vet taking up with his uncle, William “King” Hale (Robert De Niro), a cattle rancher who’s positioned himself as a beloved benefactor to the Osage. But behind his charming facade, Hale resents the tribe members for the riches to which he believes he and his white brethren are entitled, and he’s concocted a methodical plan to funnel the oil rights into his hands. When Osage members begin to die suspiciously (and, sometimes, violently), it attracts the attention of the fledgling FBI.

Grann’s book centered on FBI agent Tom White, who made a name for himself and the bureau with his work on this case (James Stewart played a character inspired by White in The FBI Story, which included a loose version of this story). Perhaps knowing that a tale about white greed wouldn’t be best served by focusing on a white savior – or understanding that there was richer dramatic material to be mined elsewhere – Scorsese and co-writer Eric Roth push White (played by Jesse Plemons) to the side and instead focus on Ernest’s marriage to Osage member Mollie (Lily Gladstone), and Hale’s manipulation of his nephew.

Masterful Filmmaking

Longtime Scorsese collaborators DiCaprio and De Niro share the screen for the first time since This Boy’s Life (1993) and deliver performances that are among the best of their careers. DiCaprio dons a nearly ever-present scowl and bad teeth to play Ernest, a not-too-bright man easily co-opted into his uncle’s scheme because of his love for women and money (at one point, Ernest confesses “I love money almost as much as I love my wife,” and it’s not entirely clear whether he’s telling the truth about his priorities). DiCaprio seems to relish portraying the less-savory sides of the character; there’s a stretch of the film where Ernest nearly collapses into self-loathing, sulking in a chair and looking like he’s going to implode. Later, in a scene where Ernest has an opportunity to come clean about his role in the conspiracy, the actor conveys more about pride and self-delusion with a quivering lip than most actors do in an entire film.

In recent years, De Niro has gravitated toward somber and quiet characters in his dramatic performances, but as Bill Hale, he reminds why he is one of the greatest craftsmen alive. On the surface, Bill Hale is a charismatic, friendly and jovial man, whose resentments and plots he keeps hidden from the public. De Niro laces the character’s energy with quiet evil and a self-righteousness that makes him one of the most memorable characters in the actor’s career. The resoluteness with which Hale holds firm to the rightness of his plan, even when he’s cornered, is chilling and speaks volumes about the ingrained sense of entitlement that fuels white supremacy.

But the film’s best performance comes from Gladstone, who conveys an entire character just with a look and a smirk. Scorsese introduces Mollie as she’s meeting with the banker who controls her funds; Mollie has been classified as “incompetent” by the government, meaning she is unable to have access to her money without the approval of a caretaker. As she spits the word out, the fierceness in her eyes and the curl of her lip show just how false that description is. Gladstone is key to the film’s emotional heart, the marriage between Ernest and Mollie. The two have a strong chemistry, and we understand why she enthralls him and why she falls for a man who is far from her intellectual equal and may, in the long run, be bad news. The early stages of their relationship are funny, sweet and moving, which makes the film all the more complex in the back half when we begin to understand just how deep Ernest’s betrayal might cut.

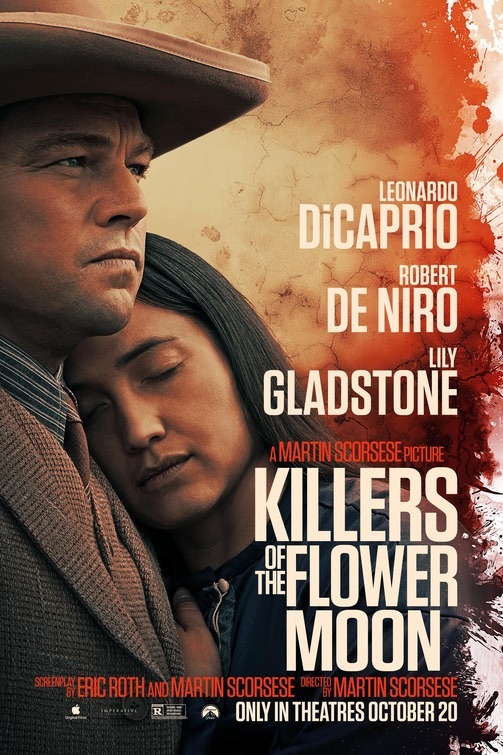

Leonardo DiCaprio and Lily Gladstone in “Killers of the Flower Moon.”

Killers of the Flower Moon’s biggest talking point has been its length. The film clocks in at nearly three-and-a-half hours, just a few minutes shorter than Scorsese’s last film, The Irishman. Like that film, Killers earns its length. Scorsese needs that time to observe the marriage between Mollie and Ernest and showcase both the genuine affection and love the two have for each other as well as the suspicion and betrayal that begins to seep in. It seems that the two genuinely like and love each other; Ernest is willing to kill and rob the Osage, but does seems to do so to provide Mollie and he a better life. But is he also knowingly poisoning his wife, or is he remaining willfully ignorant about the medicine the doctor has him administering to “slow her down”? Mollie appears to trust no one but Ernest, but as the conspiracy reveals itself, one of the film’s most heartbreaking aspects is how her trust gives way to suspicions of her own. The complex, tragic marriage is the fascinating centerpiece of the film.

The length also allows Scorsese and Roth’s script to explore the labyrinthine ways the white men attempt to keep their conspiracy afloat, sometimes biding their time through semi-legal means and other times turning to robbery, extortion and murder to speed the flow of the oil money. It might seem like I’m venturing into spoiler territory, but one of the most chilling things about Killers of the Flower Moon is how openly Hale and his cohorts flaunt their power and how aware of – and fine with – the conspiracy the white community is. When Hale takes out a life insurance policy on his Osage neighbor and jokes that he’s going to kill him for the payout, the town’s physician chuckles, and none of the non-Osage in the community are too concerned that their neighbors are dropping dead.

An Epic Story

While the length might be daunting – although the movie is only 10 minutes longer than last year’s highest-grossing film, Avatar: The Way of Water – the film never lags. Thelma Shoonmaker’s editing propels the story forward, often jumping past obligatory arrests and reveals or doubling back at just the right moment to highlight the various connections in this twisty scheme. Robbie Robertson’s score pulses beneath nearly every scene, constantly thrumming as the story unfolds. In addition to the three main characters, Scorsese gets fantastic supporting performances from Plemons – whose innate gentleness and decency keep White from being a shallow heroic cipher – as well as John Lithgow, Brendan Fraser and musician Jason Isbell. The runtime never feels like an issue of length; it, instead, gives the film depth.

In past Scorsese films like Goodfellas, Casino, The Departed and The Wolf of Wall Street, the director has been accused of glorifying his characters’ bad – even evil – behavior. While I think those charges are unmerited, I’d agree the director does have a knack for portraying violence and depravity vicariously; much of his films concern the seductiveness of crime as well as its destructive nature and the guilt that accompanies it. In The Irishman, his approach changed. The violence wasn’t thrilling or fun. It was mean, ugly and sad, and it underscored the film’s themes about the fate that awaited its characters.

In that approach, Killers of the Flower Moon seems to be in conversation with Scorsese’s last film. The film is violent – and there is one image of a crime’s aftermath that is one of the most disturbing I’ve seen – but it’s never thrilling. The death is unrelenting and matter-of-fact; often, we don’t see the murder but simply cut to the reveal of a corpse. These murders were commonplace, a tragic but common occurrence; one of them most disturbing things about the Killers of the Flower Moon is how if the murders weren’t verbally approved of, they were at least accepted among the white members of the community. It was, after all, the price of doing business and getting back what they felt they were owed. The film’s references to the Tulsa massacre and a brief shot of Ernest shaking hands with a member of the Ku Klux Klan reinforce the fact that this evil wasn’t isolated to this incident or this place. White supremacy was – and continues to be – a plague that sowed nothing but death and violence. The fact that Ernest and his cohorts weren’t particularly good at carrying out their evil deeds – the film points out that they were, in fact, pretty inept – only makes the fact that they got away with so much for so long even more incomprehensible. You don’t have to be good at crime when you have the power to get away with it.

Robert De Niro and Jesse Plemons in “Killers of the Flower Moon,” coming soon to Apple TV+.

Of course, there’s the question of whether this is Scorsese’s story to tell, a fair question to ask. And in the movie’s final 10 minutes, Scorsese addresses that while also wrestling with the idea that so much American storytelling has historically co-opted the tragedies of other people groups to transform them into stories of white heroism. The final scene plays as confession, and the cameo the movie ends on is one of its most powerful moments, allowing Scorsese to have the final word on whose story we should remember and the tale he believes should be told.

Over the last decade, at an age where he would be forgiven for retiring to Florida and playing pickleball, Martin Scorsese has directed The Wolf of Wall Street, Silence, The Irishman and now this. These are not easy films; they’re not larks. This is the work of a muscular filmmaker – one who made his first masterpieces 50 years ago – still at the top of his game with something to say. Killers of the Flower Moon might be the best of his recent works, and it joins Goodfellas, Casino, Gangs of New York, The Departed and The Wolf of Wall Street in a series of the director’s works about the dark heart that beats in American history and culture. It’s a giant, epic masterpiece that towers above most other movies released this year.

| Producer: | Dan Friedkin, Bradley Thomas, Martin Scorsese, Daniel Lupi |

| Release Date: | October 20, 2023 |

| Running Time: | 206 minutes |

| Starring: | Leonardo DiCaprio, Robert De Niro, Lily Gladstone, Jesse Plemons, Jason Isbell, John Lithgow, Brendan Fraser |

| User Rating: | |

| Writer: | Eric Roth and Martin Scorsese |

| MPAA Rating: | Rated R (for violence, some grisly images, and language) |

| Director: | Martin Scorsese |

| Distributor: | Apple TV+ |