Bill Nighy gives the performance of his career in Living as a man facing impending death with the knowledge that he’s never truly lived. His work is so good that, on its own, it’s enough to justify remaking a classic. The fact that Oliver Hermanus’ resulting film isn’t too bad itself is its own sort of miracle.

Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru (1952) has long topped many lists of the best films ever made. A moving and perceptive story about a government bureaucrat examining his life during his final days, it has much on its mind about not only the purpose of life, but also Japanese society in the 1950s. That specificity, along with Kurosawa’s masterful direction and Takashi Shimura’s compelling performance, makes it the definitive “rage against the dying of the light” movie. And while it’s inspired many other films about protagonists grappling with their mortality, few have been as powerful.

Living isn’t simply inspired by Ikiru; it identifies as a remake, and it’s a fairly faithful one. The story is transported to 1950s London, but it hits many of the same points. Nighy plays Mr. Williams, a bureaucrat whose job basically consists of shuffling problems from one department to another and ensuring that his underlings don’t try to actually engage. He’s not mean, but he’s not exactly nice. One colleague refers to him as “Mr. Zombie;” he’s breathing, but alive might not be the best word to describe him.

Early on, Williams learns he’s dying, and much of the first act involves his quiet contemplation and realization that while he has many of the trappings of “a good life,” including a well-paying job and a grown son, he abandoned zeal or passion in a quest to be a respected gentleman years ago. He heads to a resort to cash in half his life savings and live it up with a writer (Jamie Wilkes) before finding that walk on the wild side is unfulfilling. He connects with a former employee (Aimee Lou Wood) to better understand her zest for life, and ultimately decides to spend his final days completing a project that a persistent group of mothers have been shuffling to his desk for years.

It’s a fool’s errand to remake one of the greatest movies ever, and it should be noted up front that Living never quite approaches Ikiru’s level. Kurosawa’s film engages much more deeply with concerns about family and government conditions in Japan, and Living lacks the power brought by Kurosawa and Shimura. There’s nothing as bleak as the sequence where another patient tell Shimura that if a doctor says he can eat anything he wants, it means he’ll die in a few months – moments before the doctor uses those words. Hermanus lacks Kurosawa’s visual skill; although the film recreates Ikiru’s iconic final shot, it lacks that film’s sense of poetry. Shimura delivers a fierce performance, weeping under his covers, raging against impending doom; it’s a hard role to shake.

But Living finds its own quiet power. Nighy trades in Shimura’s passion for something more reserved and introspective, fitting the emotionally muted culture Williams comes from. There’s a quiet sadness in his acceptance of his fate; Williams is aware that his son wants nothing to do with him and that his work has largely been drained of meaning. He’s ill-equipped to live it up, and quickly makes peace with the fact that he’s wasted much of his life. Where many films dealing with this subject build to sequences where the protagonist roars to life, Nighy captures Williams’ internal changes more subtly. He’s stiff and expressionless for many of the earlier passages, with a more relaxed posture and warm smile taking over as Williams embraces the possibilities still available to him. Rather than try to mimic those who seem to truly appreciate life, Williams develops a quiet admiration. Even as he begins to feel vitality stir, he remains soft-spoken, dignified, and warm. It’s a great performance from an actor who regularly makes every film he’s in a bit better.

Likewise, Hermanus may lack Kurosawa’s sense of artistry, but he brings his own strengths to the table. He brings 1950s London to colorful life, and the sequences at the resort are colorful and lush. Some may find the period mannerisms a bit stuffy, but it’s an effective way of capturing the stultifying culture that shaped Williams and so many other men into the passionless creatures they are. He’s aided by a capable cast and a gentle and thoughtful script by novelist Kazuo Ishiguro, whose Never Let Me Go has its own insights about mortality.

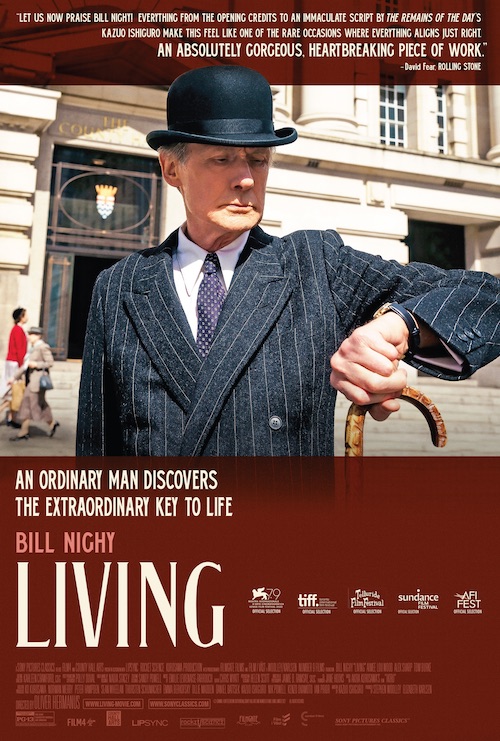

Bill Nighy in “Living.” Photo by Jamie D. Ramsay. Courtesy of Number 9 films/Sony Pictures Classics.

While Living attempts to address many of the same ideas as Ikiru, it moves at a brisker pace, clocking in at about a half hour shorter than the original. As a result, some of the subplots feel slightly robbed of their power. This is mostly noticed in the film’s final act which, as with its inspiration, deals with Williams’ coworkers and their reaction to his newfound focus and zeal. Their initial thoughts and subsequent failure to follow through feels too pat and rushed, as does the film’s depiction of a new employee (Peter Wakeling) trying to live out Williams’ life lessons. None of it is bad, but neither are these subplots engaged as well as they should be. Perhaps being a little looser in terms of fidelity could have allowed them to jettison one or two subplots and go a bit deeper on the main threads.

We’re not lacking for movies about the importance of appreciating and accepting mortality. Within the last month, in fact, it’s been the subject of two children’s films (Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio and, oddly enough, Puss in Boots: The Last Wish). But often these movies are geared toward encouraging audiences to suck the marrow out of life and not miss a single moment. But just as important are movies about the importance of examination, self-forgiveness and second chances. Ikiru is the gold standard; Living honors its themes well.

| Producer: | Stephen Woolley, Elizabeth Karlsen |

| Release Date: | January 27, 2023 |

| Running Time: | 102 minutes |

| Starring: | Alex Sharp, Adrian Rawlins, Hubert Burton, Oliver Chris, Bill Nighy, Michael Cochrane, Anant Varman, Aimee-Lou Wood, Zoe Boyle, Lia Williams, Jessica Flood, Jamie Wilkes, Richard Cunningham, John Mackay, Ffion Jolly, Celeste Dodwell, Patsy Ferran, Barney Fishwick, Tom Burke, Nichola McAuliffe |

| User Rating: | |

| Writer: | Kazuo Ishiguro |

| MPAA Rating: | PG-13 (for some suggestive material and smoking) |

| Director: | Oliver Hermanus |

| Distributor: | Sony Pictures Classics |

| External Info: | Official Site / Facebook |