Early in Saltburn, a college student defends a critique of his essay’s florid style by saying that any criticisms should be directed at the substance of the piece. It feels like a preemptive strike by writer-director Emerald Fennell, perhaps anticipating the film’s detractors will single out her in-your-face aesthetic and ignore her critique of extreme wealth. If so, her instincts are misguided; Saltburn is a gorgeous, ravishing and sensual bit of filmmaking. But it’s the script that feels empty and muddled.

Barry Keoghan stars as Oliver Quick, a first-year student at Oxford in the mid-2000s. Oliver comes from a lower-income household and has trouble fitting in with the more popular students, relegated to a table with a math nerd. Circumstances put him in the orbit of Felix (Jacob Elordi), a charismatic, handsome and rich student who takes a shine to Oliver. When family tragedy strikes, Oliver spends a summer with Felix and his family at Saltburn, their sprawling country estate, and finds himself entranced and seduced by the lavishness and decadence surrounding him. But Oliver has his own agenda and a knack for manipulation, and proceeds to insert himself in the family dynamic and hold on to Felix’s attention.

Fennell’s directorial debut, Promising Young Woman, was a sharp and provocative push back against toxic masculinity, filtered through a candy colored aesthetic. It was, at heart, a cyanide-laced black comedy, anchored by a career-best performance from Carey Mulligan and gaining relevance from its themes about female victims pushing back during a time when #MeToo permeated the culture.

Saltburn wants to be equally button-pushing and of the moment, a “Talented Mr. Ripley” for our “eat the rich” times. Fennell’s script nails the self-absorbed, image-conscious mentality of the super rich. Felix has grown up lacking for nothing and thinks he can coast by on charm alone, and amuses himself by collecting friends from less-fortunate backgrounds. His sister Venetia (Alison Oliver) has an eating disorder and lazes around the mansion all day, looking to pick up her next sexual partner. Rosamund Pike walks away with the film’s driest laughs as Felix’s narcissistic, image-obsessed mother, and Richard E. Grant wonderfully portrays a patriarch who is bored out of his mind because he’s so insulated, but lights up with joy when it’s suggested he could wear a suit of armor to a party.

It’s funny and jet black – particularly scenes involving Carey Mulligan in an extended cameo as a friend in need the family is tiring of – and it’s easy to see both why Oliver wants to be not just part of Felix’s life but this family’s, as well as why he’s annoyed by and spiteful of them (him overhearing them gossip about his family situation doesn’t help). Keoghan is quickly turning into one of our most adept actors, and he follows his lovable dimwit performance from last year’s The Banshees of Inisherin by portraying Oliver as someone who, on the surface, is lovable and naive, just wanting to fit in. But there’s also something unsettling about the way he can switch on his confidence when he understands a person’s weak point, and his obsession with Felix often manifests itself in disturbing ways (you’ll probably want to opt for showers instead of baths for awhile after seeing this movie).

But while Fennell understands how to create loathsome, troubled characters and lobs savage jokes at the elite, she doesn’t seem to know what she wants to say. Sure, the satire about equating extreme wealth with callous disinterest is on point, but it’s also obvious, and Fennell doesn’t tell an organic story so much as create interesting scenes that don’t amount to much. The script’s endpoint and the characters’ motivations are telegraphed early on, and what’s left is a lot of structure without much message. Worse, the way the film shifts its sympathies in the final 30 minutes clashes with the point Fennell seems to want to make, creating a movie where the only thing worse than the rich is the less fortunate, which seems to be an odd takeaway. In place of coherent themes are scenes designed to push buttons and send audiences out talking about how twisted the movie’s sexual politics become. And whether it’s a bloody late-night rendezvous or a fairly inappropriate attempt at graveside mourning, audiences will likely walk away talking about the movie’s provocations – and leave feeling like the movie is saying more than it really is.

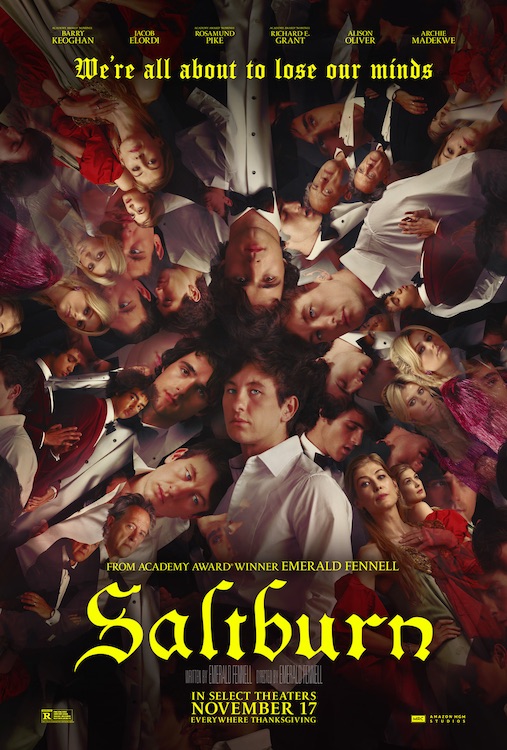

“Saltburn.” Photo by Courtesy of Prime – © Amazon Content Services LLC.

But oh, how it says nothing. Every performance, particularly Keoghan and Pike, is dialed in, darkly funny and adequately bone chilling. The use of music – particularly a final scene that will make Sophie Ellis-Bextor’s “Murder on the Dance Floor” instantly iconic – is fantastic, and the set design that brings Saltburn to life is a shadowy, crevice-infested bit of craft. And Linus Sandgren’s cinematography is rich, creating some of the most gorgeous images of the year, particularly during an extended stretch set at a Midsummer’s Night Dream-inspired party, where neon lily pads float on a lake and a boar is roasted over a spit, giving the film an otherworldly charm.

Saltburn will get people talking, even if they’re likely to discuss its surface than find anything to engage with. And during its duration, it’s a funny, unsettling and often transgressive ride. It might not succeed in saying anything new or noteworthy about the uber-rich, but it’s a ton of fun to watch it try.

| Producer: | Emerald Fennell, Josey McNamara, Tom Ackerley, Margot Robbie |

| Release Date: | November 21, 2023 |

| Running Time: | 127 minutes |

| Starring: | Barry Keoghan, Jacob Elordi, Rosamund Pike, Richard E. Grant, Archie Madekwe, Alison Oliver |

| User Rating: | |

| Writer: | Emerald Fennell |

| MPAA Rating: | R (for strong sexual content, graphic nudity, language throughout, some disturbing violent content, and drug use) |

| Director: | Emerald Fennell |

| Distributor: | MGM |

| External Info: | #SALTBURN |