For all the critical and technical acclaim that was heaped on director James Cameron’s Titanic upon its release in 1997, there were still quite a few people that really weren’t all that impressed. Still, it went on to become the highest grossing film of the year and one of the most popular films of all time. Now, twenty-five years later, the film still rests in third place on the list of worldwide lifetime grosses – just ahead of the director’s recent Avatar: The Way of Water (2022) and behind 2009’s Avatar at number one. It remains remarkable how captivated audiences still are by this tragic tale of love told amidst the most famous shipwreck in history.

That James Cameron would make Titanic was inevitable, since the director of such blockbusters as Aliens (1986), Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991), and True Lies (1994) once likened filmmaking to creating “spectacles,” and what spectacle (at the time of its release) has proven costlier, grander, or more popular than Titanic? It is also appropriate that the pre-Avatar stage of Cameron’s career was capped by the biggest cinematic spectacle he (or anyone else for that matter) had yet created. Indeed, the film brought in an overwhelming worldwide box office of $1.8 billion (a total that grew exponentially when added with a $30 million television sale, $400 million for the over 25 million copies of the soundtrack that have been sold; and somewhere north of $700 million in global video sales when all was said and done). The unequaled box-office success Titanic has enjoyed in addition to the critical praise heaped upon it (it tied All About Eve (1950) with a record 14 Academy Award nominations and consequently went on to win a record 11 including Best Picture and Best Director – tying Ben-Hur [1959]) indeed transformed Titanic into something more than a mere movie, it has since become a cultural phenomenon.

The production story of Titanic (an epic on par with the film itself) began when Robert Ballard discovered the wreckage of the ship in 1985 on the ocean floor 400 miles off the coast of Newfoundland. Upon seeing the National Geographic documentary on the discovery, Cameron developed the following story idea: “Do story with bookends of present-day [wreckage] scene … intercut with memory of a survivor … needs a mystery or driving plot element.” Then, in early 1995, Cameron made the initial pitch to studio executives. A pitch which was reluctantly accepted based on the director’s track record of profitability as well as the fact that he was maintaining that the film could be made for less than $100 million. In late 1995, as a precursor to the start of formal production, Cameron made 12 two-and-a-half mile descents to the Titanic wreckage site where he used a specifically designed 35mm camera to obtain footage for the bookend sections of the film. Armed with this footage, Cameron next had to convince the studio to back the film wholeheartedly. After the project was officially green lit in May 1996, ground was broken on a studio in Rosarito Beach in Baja California, since it had been determined some months prior that no one studio in the world could provide the facilities needed for the mammoth project. This custom-built studio featured a 17-million gallon exterior shooting tank (the largest in the world) which housed the 775 foot-long, 90% to scale replica of the Titanic; a five-million gallon interior tank housed on a 32,000 sq. ft. soundstage; three other stages; production offices; set/prop storage; a grip/electric building; welding/fabrication workshops; dressing rooms; and support structures.

During this time, Fox was seeking a partnership with other studios to alleviate the film’s already considerable financial risk. After pitching the deal to a few studios, Paramount agreed to co-finance the film (but they would ultimately limit their contribution to $65 million). Production on the film finally began in September 1996. Soon after the start of production, rumors were circulating regarding the expensive production, which would eventually jump from 138 to 160 days; the less-than-stellar working conditions some crew members likened to sweatshops (some even complained of having to work as long as two weeks without a break); unconfirmed accidents on the set; an infamous food-poisoning incident when the cast and crew were accidentally served food laced with PCP; as well as the usual screaming tirades from the compulsive director. Cameron and company also went to great lengths to ensure the historical authenticity of the film. It is through these technical aspects (i.e., the set decoration, costumes, etc.) that the film excels on an epic scale. When production finally wrapped in March 1997, over 12 days (288 hours) of footage had been shot. As Cameron secluded himself in the editing room, 18 special effects houses went to work on the more than 500 visual effects shots that the film would eventually require (a process that would take them the next several months to complete). Originally slated to open on July 2, Titanic was pushed to December after it became clear that Cameron was nowhere near being done with the arduous editing process. When all was said and done, Titanic was released on December 19 to maximize its Oscar chances. The total shooting cost for the film was estimated at just over $200 million.

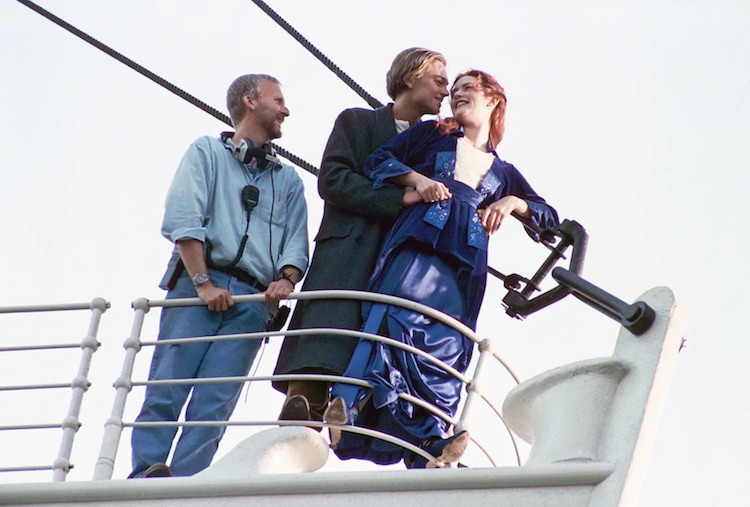

James Cameron (from left), Leonardo DiCaprio, and Kate Winslet on the set of “Titanic.” 20th Century Fox/Paramount Pictures.

Titanic tells the fictional story of two class-crossed lovers who meet aboard the disaster-bound ship, fall in love, and then struggle to survive the grizzly sinking all within the context of a true-to-detail retelling of the actual disaster. This story within the film is launched from the present-day via a subplot that revolves around a missing diamond (the completely fictional “Heart of the Ocean”). After treasure-hunter-for-hire Brock Lovett (Bill Paxton) finds a drawing of a naked young woman wearing the elusive diamond and features it in a television program on which he is appearing, an elderly woman (Gloria Stuart as a 101-year-old Rose) comes forward claiming to be the woman in the picture. After being whisked to the Titanic wreck site, Rose proceeds to recount the story of the ship’s fateful voyage. It is here that a slew of stock characters are introduced: Jack Dawson (Leonardo DiCaprio) is the American, free-spirit archetype from the wrong side of the tracks; Rose DeWitt Bukater (Kate Winslet) a beautiful Philadelphia socialite who has no control over the course of her life; “Cal” Hockley (Billy Zane), Rose’s oppressive husband-to-be who sees her as nothing more than a possession; and Rose’s domineering mother Ruth DeWitt Bukater (Frances Fisher) who views Rose’s marriage to Cal as vital to the family’s survival and Rose’s burgeoning romance with Jack as a threat to her current way of life. The romance between Jack and Rose begins when he thwarts her attempted suicide and infiltrates her first-class lifestyle. Slowly, Jack entices Rose to let go and to, as the film ensures we remember, “make it count.” Their relationship culminates in the creation of the aforementioned “drawing” and a torrid bit of lovemaking. Titanic then hits the iceberg, and the film shifts from romance to an action-adventure. The final act of the film concentrates on the sinking of the ship and Rose and Jack’s quest for survival. After some of the greatest special effects ever put on film (at least to date in 1997), Titanic sinks and Rose is left atop a piece of wood while Jack floats nearby slowly freezing to death. While they wait for rescue, Jack makes Rose promise that she “won’t give up, no matter what happens, no matter how hopeless.” After being rescued and reaching America, Rose takes the name of Dawson and lives the life that she promised Jack she would. The film then bounces back to the present-day salvage ship to deliver the film’s coda, wherein Lovett declares that although he’s been searching for Titanic he never “got it.” Later that evening, Rose makes her way to the deck of the ship and drops the “Heart of the Ocean” necklace into the sea. Rose dies peacefully in her sleep (“an old lady warm in her bed,” just as Jack had predicted) later that night surrounded by the photographic memories of the life she had thanks to Jack. Upon her death, she is transported back to Titanic (presumably her entrance to the afterlife) and reunited with Jack, as well as all of those who died aboard the ship, at the grand staircase (where the clock reads 2:20 – the time of Titanic‘s sinking). She appears in this sequence as her 17-year-old self, thus suggesting that this is, as Dave Kehr wrote in the New York Daily News, “the time it will always be: [both] the beginning of her life and its end.”

Before addressing the critical worth of Titanic, it is important to discuss the nature of its immense popularity. Perhaps the weakest explanation for Titanic’s popularity would lie in an offhand comment by Cameron himself wherein he referred to the film as nothing more than a “$190 million chick flick.” Although it is true that scores of women (mostly teenage girls) flocked to see this movie less for the special effects or sensational movie making than for the charismatic DiCaprio and the way he swept Winslet off her feet, to categorize the entire film as a so-called “chick-flick” does it a disservice. Instead, the appeal of Titanic exists in the relationship the audience has with the story of the film itself. That is, the film functions almost as a parable for the American Dream and the American way of life.

A still from “Titanic.” © 1997 – Paramount Pictures.

The core of the film is an epic romance. Cameron has long said that this was the “great love story” he thought The Abyss (1989) should have been. While the love story appears to be the heart of the film it is, however, the anachronistic characters of Jack and Rose that make the film so appealing to a modern audience. These two characters serve, as Peter N. Chumo noted in “Learning to Make Each Day Count: Time in James Cameron’s Titanic,” in Journal of Popular Film and Television, Winter 1999, as the “audience’s surrogates.” That is, neither character is particularly correct for the time period of the film, they are more like modern interpretations of a princess and a young rogue. Yet they are more than mere stereotypes. Both characters are archetypes of the American consciousness: Rose being the enlightened woman of the 20th century and Jack being the adventurous American male. The way these modern characters function within the timeframe of the film is what endears them to the audience, and it is also what makes the film more a lesson in morality than a retelling of history. It is for this reason, as Mike Pence has pointed out in “Explaining the Appeal of Titanic,” in the Saturday Evening Post, May 1999, that “what draws us to this film is an undeniable sense that we are seeing America of the late 20th century in metaphor before our eyes.”

The critical reception Titanic received was for the most part positive, but there was a faction that detested the film, and it is this that causes the film’s critical worth to be in question even today after all its success and accolades. Much of the post-Oscar lambasting of Titanic can be traced to the backlash over the snub of L.A. Confidential (1997) in favor of Titanic in the categories of Best Picture and Director. The general opinion was that Oscar voters felt that if they didn’t go along with the popular opinion then they would be subject to profound criticism. So, when the big box-office winner also won the two biggest awards, the assumption was that the Academy had been taken in by the hype and had been pathetically swayed by public sentiment. But this is a very close-minded argument when one considers for a moment that Titanic was actually a pretty good movie. Curtis Hanson (the director of L.A. Confidential) elaborated on this very point when he stated, “As Frank Capra said, don’t make your best movie the year somebody else makes Gone with the Wind.” Does this mean that Gone with the Wind shouldn’t have won Best Picture because Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (both were released in 1939) had a better story, better characters, or even better acting, yet was considerably less popular than its competitor? Each film exists on its own terms, and each is a fine piece of cinema. The inability to come to terms with this undeniable fact is the cause of division among critics and film scholars about Titanic. This does not mean that Titanic is free of flaws. One thing that stands out as subpar is the crude often inelegant dialogue of the script. (A problem that has plagued Cameron in all his films but has gone relatively unnoticed until he decided to do a period specific romantic epic in which his writing style is not a comfortable fit at all.) As Corie Brown and David Ansen suggested in Newsweek, “Rough Waters: The Filming of Titanic,” December 15, 1997: “Cameron should have lavished more of his perfectionist’s zeal on his dialogue.” Logically speaking, several script problems exist within Titanic besides dialogue. For example, if the story is being related to us by Rose, how can she know anything about Jack before having met him during her attempted suicide (are his actions embellished by her to befit her memory of him?). Also of note are other instances wherein Rose recounts dialogue and actions she could have had no knowledge of (i.e. the framing of Jack by Cal or the decision by J. Bruce Ismay to push the engines as hard as they could go).

Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet in “Titanic.” © 1997 – Paramount Pictures.

Although it can be argued that the acting throughout the film is at times wooden and merely meant to bring life to what amounts to simply stock characters (DiCaprio’s Jack, throughout the first half of the film, stands out in this regard) none of these characters become, as Richard Corliss, in Time (New York), December 8, 1997 accused them of being, “caricatures … designed only to illustrate a predictable prejudice: that the first-class passengers are third-class people, and vice versa.” These so-called caricatures never work against the audience, forcing a dislike of the film on the grounds of insulting their intelligence. Consider this: Titanic achieved the level of popularity it did without the help of a single international box-office star (although it certainly created one in DiCaprio). Certainly this must attest to the entertaining value of the film. One thing that cannot be disputed is that once Titanic hits the iceberg 100 or so minutes into the film, the next 80 minutes are as thrilling as any action-adventure film has ever been (and is where Cameron shines). When combined with the romantic epic nature of the film, Titanic, as Owen Glieberman stated in Entertainment Weekly (New York), December 19, 1997, “floods you with elemental passion in a way that invites comparison with the original movie spectacles of D.W. Griffith.”

All this is not to say that Titanic is a work of art, it has its problems. It is poorly written (note that it was not nominated for an Oscar for Best Screenplay) and is at times rather shabbily acted (but hasn’t somebody made that same argument about Gone with the Wind at some point in history?). Cameron certainly didn’t help his own critical standing when he blasted Kenneth Turan of the Los Angeles Times in print for writing an unflattering review of Titanic. But, where the film does succeed is in being a flat out good movie. It is enjoyable, pure and simple. Surely, nobody can doubt that Titanic is one of the most successful films in history, and no one can dispute that the film boasts some of the most spectacular effects ever put on film (in fact, apart from Best Picture and Director awards, all the Oscars that Titanic won had something to do with the film’s technical accomplishments). But, does all of this mean that it deserved to win Best Picture and Director over L.A. Confidential? That’s a matter of opinion and endless debate. Perhaps another 25 years down the road we will have a completely different consensus regarding Titanic than the argumentative one we still have today.