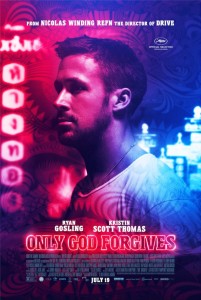

| Release Date: | July 19th, 2013 |

| Starring: | Ryan Gosling, Kristin Scott Thomas, Vithaya Pansringarm, Gordon Brown, Yayaying Rhatha Phongam |

| User Rating: | |

| Writer: | Nicolas Winding Refn |

| MPAA Rating: | R |

| Director: | Nicolas Winding Refn |

Reprehensible, pedophilic murderers are not usually the brand of character that is the focus of a revenge vendetta. If I am going to be encouraged in the course of a film to root for retribution for the fallen, then give me the opening slaughter of the family in Once Upon a Time in the West or “The Bride’s” wedding day massacre in Kill Bill. Revenge may be a tried and true motivation in the history of action thriller cinema, but few films have a more amoral bent than the ugly/beautiful Only God Forgives – hot director Nicolas Winding Refn’s follow-up to his Michael Mann-ish 1980s-flavored hit Drive. As Drive proved to be a master class in substantive style with enough humor and heart to keep the human stakes raised, interest in Refn’s art house macho approach to weathered crime film tropes was peaked and his next project was anticipated by a new cult of fans.

This would all be very Zen and interesting in the era of explosions and artillery if Only God Forgives seemed to care about the interior lives of the characters (each one a hollow sketch with one or two distinguishing attributes) or the final consequences of the escalating bloody battles (the anti-climactic throw down at the end is especially humorous and aggravating in defying expectations of closure or catharsis).

Shooting a dramatic action film with European and Asian art film techniques is nothing new, but Refn is an undeniably good structural filmmaker – the slow motion he favors, borrowed from the style of Fassbinder, Wong Kar-Wai, and Chinese wushu pictures adds to an operatic rhythmic flair making uneasy, interesting bedfellows with the bloodlust urge that erupts in cringe-inducing violent sequences (the hammer and elevator scenes in Drive and Tom Hardy’s insane outbursts as Bronson are one-upped in this film but with none of the emotional connection that made the former movies’ brutalities linger with uneasy, complicated satisfaction).

By removing the human element (aside from a couple of baffling sequences with the head cop singing soft karaoke to his enthralled troops and a late-hour sparing of a marked-for-death child), Refn has scaled back his essentials to a series of entrancing tracking shots, multi-colored lighting schemes, and the heavy hum of Cliff Martinez’s droning score – technical elements pointing toward a better film – a descent into brutal codes of organized crime and martial artistry lost in obscuring technique. That was the promise of this exciting director fashioning his story around the world of Thai kickboxing and Asian honor debts; instead he a made a pretty, dull, and confusing immorality play that maintains a stance of aloof, mute cool in place of a coherent screenplay with fully-formed concepts and goals. In this way, the movie belongs to a strain of experimental film interested in reducing reliance on the text and going for the aesthetic thrills of “pure cinema.” On that front, it is a marvelous achievement in showing off an art direction full of gorgeous urban squalor to rival the salacious look of Gaspar Noe’s films.

[springboard type=”video” id=”701291″ player=”cnim002″ width=”560″ height=”315″ ]

Like Noe’s ultimately-empty Enter the Void, Only God Forgives suggests in its title a contemplative quality that I could not detect in the film’s body. At certain points, Gosling’s character descends into a kind of mind warp reminiscent of what Fred goes through in David Lynch’s Lost Highway; it leads us to make justifications that the movie is perhaps existing on an unreal plane (it does maintain an admirable internal logic) that holds greater mysteries of identity and moral dilemma not present in the real-time action and therefore remains open only to those willing to extrapolate a higher purpose in what is essentially an anti-narrative, non-action action movie that will satisfy few.[box_info]WHERE TO WATCH (powered by JustWatch)

[/box_info]

OGF

Ugh, another idiot who didn’t get this masterpiece. No surprise.

tristan eldritch

Right on.